This is an on-going serialisation we are doing of a great little book called, ‘A history of community asset ownership’ by Steve Wyler who has kindly agreed for us to reprint his book on our website. We think a much better title for the book would be ‘The UK common peoples history’. We at Permanent Culture Now were going to do a very similar take on History that Steve has done with his book, so when we saw it we were like that’s great someone has already done the hard work. So we are expanding the work by adding our views as to why this history is relevant for today, drawing parallels with then and now and taking from it inspiration for building a more permanent culture.

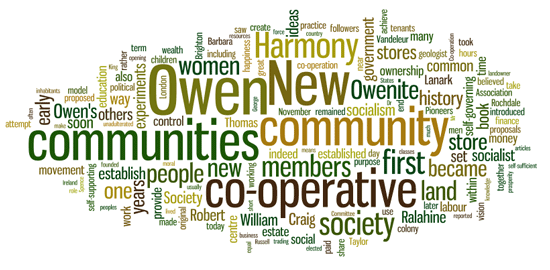

A common peoples history of the UK part 5: Villages of co-operation

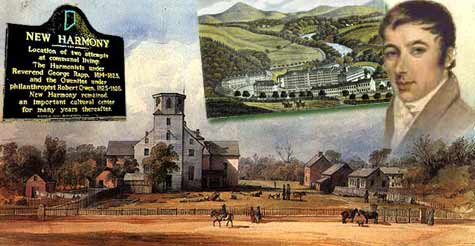

In the early 1800s Robert Owen introduced reforms at New Lanark in Scotland and went on to establish a co-operative community at New Harmony in the United States. Owen’s vision was of a society made up of a commonwealth of self-governing and self-sufficient ‘villages of co-operation’, each of around 1,000 people, where sectarian religious views would not be allowed to take hold, and industry and enterprise for the common good would provide prosperity for all. New Harmony was short lived but it stirred the imagination: many experiments followed and some such as Ralahine in Ireland held high promise. The first co-operative store was founded in Brighton by Dr William King in 1827, not as an end in itself but rather as a means to finance these ‘socialist’ communities.

In the early 1800s Robert Owen introduced reforms at New Lanark in Scotland and went on to establish a co-operative community at New Harmony in the United States. Owen’s vision was of a society made up of a commonwealth of self-governing and self-sufficient ‘villages of co-operation’, each of around 1,000 people, where sectarian religious views would not be allowed to take hold, and industry and enterprise for the common good would provide prosperity for all. New Harmony was short lived but it stirred the imagination: many experiments followed and some such as Ralahine in Ireland held high promise. The first co-operative store was founded in Brighton by Dr William King in 1827, not as an end in itself but rather as a means to finance these ‘socialist’ communities.

In the early 1800’s Robert Owen, a part owner of cotton mills at New Lanark near Glasgow, became shocked at the conditions of the workforce and their families and resolved to do something about it. He believed that education was the solution, and opened a school at New Lanark which he described as an ‘Institution for the Formation of Character.’ At the school’s opening ceremony he declared that ‘no obstacle whatsoever intervenes at this moment’ to create a healthy society free of crime and poverty, ‘except ignorance’. (24) Working class children (both girls and boys) were taught during the day and older children and adults in the evening; lessons included dancing, exercises, music and singing, and in summer excursions were made into the countryside.

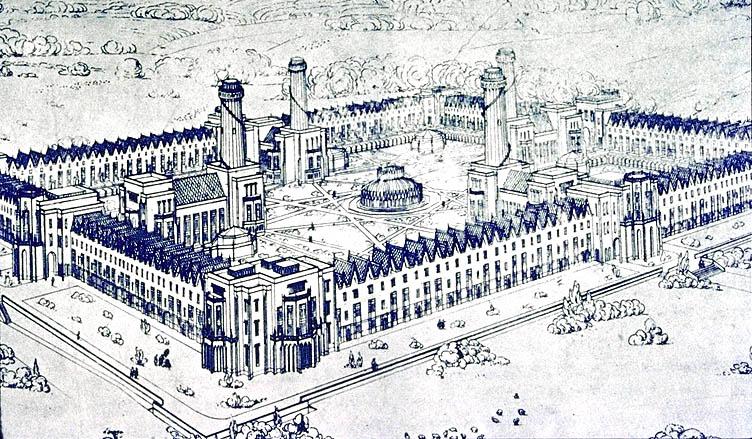

The scheme attracted interest, and at first Owen expected that his example would be enthusiastically taken up by others within the ruling classes. This was not to be. However, a new opportunity came in 1817: alarmed by mass unemployment in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, and a rise in social unrest, the government was desperate for solutions. Owen was invited by the Archbishop of Canterbury and subsequently by a Parliamentary Committee on the Administration of the Poor Laws to set out his ideas. In 1819 the Committee published a diagram of Owen’s proposals inscribed ‘A view and plan of the Agricultural Villages of Unity and Mutual Co-operation’.

The scheme attracted interest, and at first Owen expected that his example would be enthusiastically taken up by others within the ruling classes. This was not to be. However, a new opportunity came in 1817: alarmed by mass unemployment in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, and a rise in social unrest, the government was desperate for solutions. Owen was invited by the Archbishop of Canterbury and subsequently by a Parliamentary Committee on the Administration of the Poor Laws to set out his ideas. In 1819 the Committee published a diagram of Owen’s proposals inscribed ‘A view and plan of the Agricultural Villages of Unity and Mutual Co-operation’.

Owen proposed that society should be transformed into a series of communities, with an ideal population of 800-1,200. Each was to be self-supporting and their members would be engaged in various branches of manufacture and agriculture. There should be enough land to supply the needs of the village, and to produce a surplus allowing trade with other communities. The villages would be located in the centre of farmland, and the layout would encourage a communal way of life. A parallelogram was proposed, avoiding traditional streets and alleys that Owen believed were damaging to health and a source of crime.

Owen’s belief in the force of rational persuasion made him confident that capital to create the first communities would come from industrialists, landowners, parishes and counties, and groups of farmers, mechanics and tradesmen. However, the immediate reaction of the establishment was disappointing. While Owen indeed found several influential supporters including the Duke of Kent, the economist David Ricardo and Sir Robert Peel, he also encountered vehement opposition from others including Wilberforce and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. An attempt to establish a select committee to get the plan underway was heavily defeated by 141 votes to 17.

New Harmony

In November 1824 Owen turned his sights towards America. With $135,000 of his own money he purchased an existing colony in Indiana capable of housing 800 people. New Harmony, as the colony was renamed, would become the model for a ‘New Moral World’. Here, Owen adopted the ideas of Josiah Warren, an American anarchist who lived for a while at New Harmony and other Owenite communities, and who had set up the first time store. Labour was to be the new currency, and New Harmony produced its own banknotes representing hours of labour.

Owen was determined that New Harmony should exert an educative force not just on its own inhabitants but on society at large. The key was to attract scientists of the highest calibre and in this Owen was remarkably successful. In 1826 William Maclure, a wealthy Scottish geologist and educationalist, sent out his private library, philosophical instruments, and collections of natural history. These were accompanied by a party of scientific associates, including the geologist Gerhard Troost and the naturalists Charles Lesueur and Thomas Say. They travelled together to New Harmony by keel-boat from Pittsburgh – a ‘boat-load of knowledge’.

Owen was determined that New Harmony should exert an educative force not just on its own inhabitants but on society at large. The key was to attract scientists of the highest calibre and in this Owen was remarkably successful. In 1826 William Maclure, a wealthy Scottish geologist and educationalist, sent out his private library, philosophical instruments, and collections of natural history. These were accompanied by a party of scientific associates, including the geologist Gerhard Troost and the naturalists Charles Lesueur and Thomas Say. They travelled together to New Harmony by keel-boat from Pittsburgh – a ‘boat-load of knowledge’.

Maclure’s aim was to make New Harmony the ‘centre of education in the west’. His enthusiasm had a deep impact on Owen’s sons, and one of them, David Dale Owen, became a prominent geologist. The young Abraham Lincoln saw the colonists pass up the river on their way to New Harmony and unsuccessfully begged his father to let him join them.

Early co-operative communities

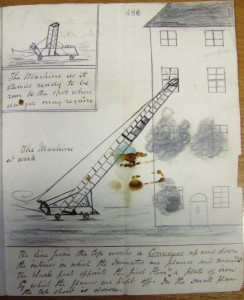

Owen’s ideas and activities in the United States stimulated a series of further experiments. Some were ill-conceived and quickly vanished, but all contributed to a growing pool of skills and knowledge. In Spa Fields in London in the 1820s Owen’s followers took steps to research and measure social impacts; at Orbiston in Scotland a substantial community was established; early attempts at co-operation in Devon were begun but soon abandoned; a colony at Graveley near Brighton had more success. At Manea Fen near Cambridge, a settlement which Owen discouraged, a windmill was erected named Tidd Pratt, in honour of the Registrar of Friendly Societies (the windmill was completed on the day the community received its certificate of incorporation).

The most promising of the early Owenite experiments was at Ralahine in County Clare. In 1831, in an attempt to prevent secret societies from recruiting his discontented tenants, an Irish landowner John Vandeleur persuaded an Owenite socialist Thomas Craig to establish a co-operative society on his estate of 618 acres at Ralahine in County Clare. When Craig arrived he learned that the previous manager had been shot dead by the tenants, and Craig was greeted by an anonymous note in which was depicted a skull and crossbones, together with a warning that he too would soon be put to bed under the ‘daisy quilt’.

Nevertheless, it was not long before the tenants were won over by Craig’s proposals. The community established by Craig consisted of forty-six people and was self-governing: a managing committee of nine was elected twice a year. The aims of the New System, as it became known at Ralahine, were to acquire common wealth to protect members against the evils of old age and sickness, to achieve mental and moral improvement of adults, and to educate children. Alcohol, tobacco and snuff were banned, as was gambling of any kind. The members of the community had to work twelve hours a day in summer and from dawn to dusk in winter, with a one hour break for dinner. They ate meals together, and a school was established.

Nevertheless, it was not long before the tenants were won over by Craig’s proposals. The community established by Craig consisted of forty-six people and was self-governing: a managing committee of nine was elected twice a year. The aims of the New System, as it became known at Ralahine, were to acquire common wealth to protect members against the evils of old age and sickness, to achieve mental and moral improvement of adults, and to educate children. Alcohol, tobacco and snuff were banned, as was gambling of any kind. The members of the community had to work twelve hours a day in summer and from dawn to dusk in winter, with a one hour break for dinner. They ate meals together, and a school was established.

Instead of money the workers were paid in cardboard vouchers representing a day’s work, worth 8d and about the size of a gentleman’s visiting card. Fractions of these down to sixteenths were recognized and so were multiples, and they could be spent in the co-operative store which provided healthy and unadulterated food, thus ensuring that wealth as far as possible remained in circulation within the community. If the members wished to spend money outside the commune they could exchange the labour notes for coin. All members of the community over the age of seventeen took a share in the division of profits. The estate prospered and a further twenty nine people joined. New machinery was bought and the first mowing machine in Ireland was introduced.

After two years, however, the experiment collapsed, but through no fault of the community itself. The landowner Vandeleur lost all his possessions through gambling, and because he had retained ownership of the estate (the community paid an annual rent) the land was seized and the community was evicted. The members met for the last time on 23 November 1833 and placed on record a declaration of ‘the contentment, peace and happiness they had experienced for two years under the arrangements introduced by Mr. Vandeleur and Mr. Craig and which through no fault of the Association was now at an end.’

Ralahine remained a beacon of hope. Seventy years later Alfred Russell Wallace praised its practice of self-government: ‘it was found that the most ignorant of labourers were sometimes able to make suggestions of value to the community… it shows that sufficient business capacity does exist among very humble men as soon as they have the opportunity of practising it.'(25)

A new moral world

Co-operative Community’ which was moored on the Thames, where it was thought the inhabitants would be safe from the extortions of retail traders, lodginghouse keepers, and gin shops. In the same year it was reported that community coffeehouses existed in London.

Owen himself suggested that the government should purchase the new railways and the land by the side of them up to six miles broad so that communities could be established as the railways developed, thus capturing increased land value for public benefit. The suggestion was, unfortunately, not acted upon.

In New Harmony, Owen had proposed a new role for women. With child-rearing, cooking and washing transferred to the community, women could play a role in factories and gardens, and take an equal share in communal tasks. Owen also took a reformist position on marriage, attacking impediments to divorce, and for this he was much condemned by the establishment. Owen was not the first to combine the political and social emancipation of women with proposals for a society based on small communities – Mary Wollstonecraft in 1790 (26) and Thomas Spence in 1797 (27) had sketched out just such a vision. But it was Owen and his followers who were to develop these ideas further and indeed attempt to put them into practice. The atheist Emma Martin believed that only Owenite socialism could remove the great evil of the ‘depraved and ignorant condition of women’, (28) and William Thompson saw in co-operative communities the means to achieve perfect equality between men and women:

In New Harmony, Owen had proposed a new role for women. With child-rearing, cooking and washing transferred to the community, women could play a role in factories and gardens, and take an equal share in communal tasks. Owen also took a reformist position on marriage, attacking impediments to divorce, and for this he was much condemned by the establishment. Owen was not the first to combine the political and social emancipation of women with proposals for a society based on small communities – Mary Wollstonecraft in 1790 (26) and Thomas Spence in 1797 (27) had sketched out just such a vision. But it was Owen and his followers who were to develop these ideas further and indeed attempt to put them into practice. The atheist Emma Martin believed that only Owenite socialism could remove the great evil of the ‘depraved and ignorant condition of women’, (28) and William Thompson saw in co-operative communities the means to achieve perfect equality between men and women:

This scheme of social happiness is the only one which will completely and for ever ensure the perfect equality and entire reciprocity of happiness between women and men. (29)

In practice, Owenite communities fell short of perfection; while women usually had voting rights within the communities, and benefited from education on an equal basis, the communities remained largely male-dominated, and the apportionment of labour often resulted in women working longer hours. (30)

Co-operative trading

The Owenite experiments gave birth to a movement of co-operative stores. In 1827 Dr William King became convinced that a co-operative shop could provide the money to finance a community, and set one up in Brighton for this purpose. This was the beginning of the co-operative stores movement. 31 Just three years later it was reported that already 300 were operating across the country. A co-operative journal Common Sense described the purpose of a trading association:

The object of a Trading Association is briefly this: to furnish most of the articles of food in ordinary consumption to its members, and to accumulate a fund for the purpose of renting land for cultivation, and the formation thereon of a co-operative community. (32)

But often the stores became an end in themselves, and the original impulse, to provide finance for new Owenite communities, was lost, and many of the stores failed.

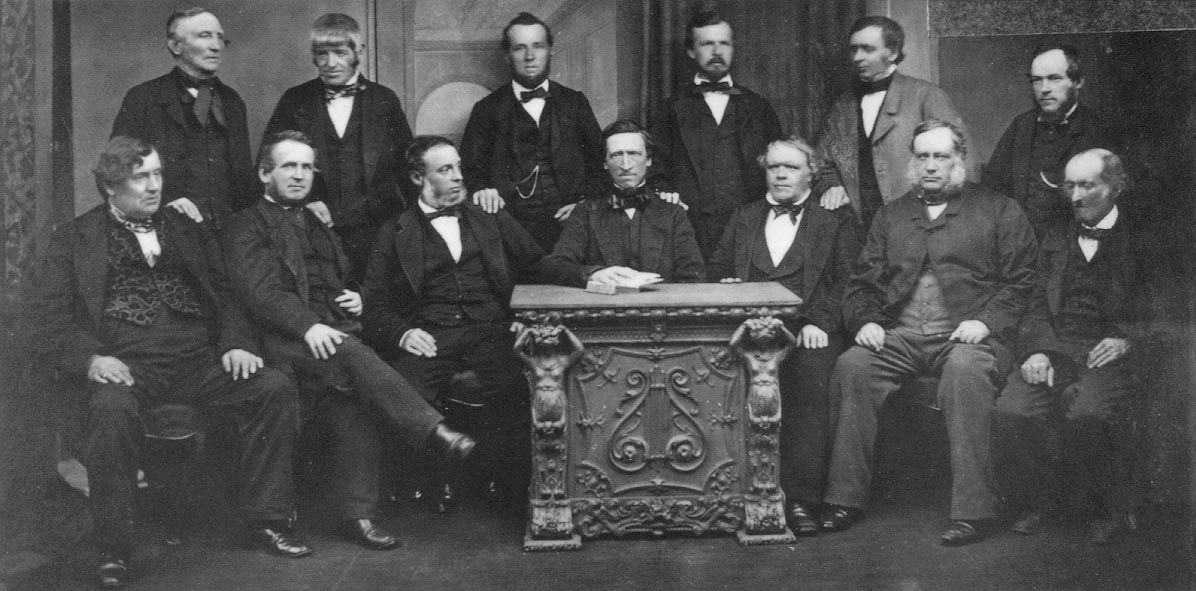

In 1844 new life was imparted into this movement by a group of 28 weavers and other working people who set up ‘The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers’ opening a small grocery store in Toad Lane, selling only unadulterated goods. They invented a new form of business, whereby the customer became a partner in the rewards of mutual endeavour: they refused to give credit to customers, but for the first time paid them a share of profits (a ‘dividend’). The Rules of the Society became a model for others, and within a decade there were nearly 1,000 co-operative stores operating on similar principles across the country.

As with the first co-operative stores the aim was to create fully self-supporting communities, on land which they themselves would own:

As a further benefit and security to the members of this society. the society shall purchase or rent an estate or estates of land, which shall be cultivated by the members who may be out of employment, or whose labour may be badly remunerated.

That as soon as practicable, this society shall proceed to arrange the powers of production, distribution, education, and government, or in other words to establish a self-supporting home-colony or united interests, or assist other societies in establishing such colonies. (33)

The Society encountered many problems in its formative years, but the characters of the initial pioneers were decisive in overcoming these problems, and not least of their qualities was humour:

Of the ‘Famous Twenty-eight’ old Pioneers, who founded the store by their humble subscriptions of twopence a week, James Smithies was its earliest secretary and counsellor… In the presence of his vivacity no one could despond, confronted by his buoyant humour no one could be angry. He laughed the store out of despair into prosperity.

His ‘laugh was like a festival,’ and he kept the movement ‘merry in its struggling years’. (34) A descendent, Keith Smithies, works at the Development Trusts Association today.

The true socialism?

The term socialism today usually implies a political system in which the state takes centre stage, nationalising land and other natural resources, directing manufacturing and commercial activities, and using wealth produced by the people to provide them with goods and welfare services according to their needs. The original use of the term was very different, indeed was wholly opposed to the notion of a dominant controlling state. The first documented use of ‘socialist’ in the Oxford English Dictionary is in a letter in The Cooperative Magazine, London, November 1827. There it referred to the ideas propagated by Robert Owen and his followers that society should consist of a federation of self-governing and largely self-sufficient communities.

The term socialism today usually implies a political system in which the state takes centre stage, nationalising land and other natural resources, directing manufacturing and commercial activities, and using wealth produced by the people to provide them with goods and welfare services according to their needs. The original use of the term was very different, indeed was wholly opposed to the notion of a dominant controlling state. The first documented use of ‘socialist’ in the Oxford English Dictionary is in a letter in The Cooperative Magazine, London, November 1827. There it referred to the ideas propagated by Robert Owen and his followers that society should consist of a federation of self-governing and largely self-sufficient communities.

When many of the early co-operative experiments failed, others started to look towards action by central government rather than local communities to establish common or mutual ownership. For some the way to achieve this was through universal suffrage and political control of  Parliament. For others the route to socialism was through armed insurrection and mass revolution. But either way the goal was to seize power at the centre and direct the resources of the nation, through machineries of command and control. Marx and Engels wanted to use the term socialist rather than communist in their 1848 manifesto, but they realised it would have created a confusion with the Owenite version which was at that time still current, though soon to be overshadowed by the Marxist usage and a little later by that of the Fabians.

Parliament. For others the route to socialism was through armed insurrection and mass revolution. But either way the goal was to seize power at the centre and direct the resources of the nation, through machineries of command and control. Marx and Engels wanted to use the term socialist rather than communist in their 1848 manifesto, but they realised it would have created a confusion with the Owenite version which was at that time still current, though soon to be overshadowed by the Marxist usage and a little later by that of the Fabians.

The Fabians constructed a model of socialism which they claimed could be achieved through a programme of nationalisation and delivery of welfare services directed by national government, with some tasks delegated to local municipalities elected by the people, but with effective control in the hands of those who knew best, the professional classes. A long way indeed from the original socialist vision that working people could live and prosper in self-governing and co-operative communities, where they exercised ownership and control.

Robert Owen idea of self governing and self sufficient communities resonates throughout history as it has ideas that have been the basis of many alternative experiments in living from 1960’s communes to the eco-villages of today. Although short lived it also inspired the ideas of cooperatives with the first cooperative store being founded in Brighton. So the influence of Owen is felt throughout many realms, but I doubt that all the people influenced by these ideas know about Owen. So today we see hundreds of thousands of cooperatives in operation and loads of experiments in alternative living through intentional communities.

Owen also believed that education was key to a healthy society, something that we fully endorse at Permanent Culture Now, though we believe that most mainstream education is not particularly fulfilling as it replicates the unequal structures of society and is focused on creating workers for the capitalist mode of production rather than developing critical thinking individuals, although I am sure that Owen would probably agree with this. Education when it is for the development of human beings can be a wondrous thing and we believe that there are many forms of education that attempt to do this. Owen not only focused learning on children he also believed in educating adults as well and we believe that you never stop learning as life is one long process of learning from the day your born to the day you die.

Owen interestingly was more of a reformer and he sought to change society through interaction with the ruling class of the day. Not surprisingly they were not particularly supportive of his models, more than likely because they threatened their position. Why would the ruling class want a healthy educated working class, surely they would begin to question the structure of society and be keen for a more equal stake within it. This dilemma resonates throughout history and I believe that the reason we see more and more questioning of establishments the world over is because we have had a more educated general population who are challenging unequal power structures, be it through the Occupy movement or the Arab uprisings, more and more people are critical of the ruling classes.

Owenite communities such as the Ralahaine community in County Clare, had the seeds of a basic welfare state, where they had been thinking about how to protect people against sickness and old age, as well as educating their members. You have to remember that in those days these were not mainstream, so it was quite radical to be thinking in that way.

They also had their own local currency, another idea that has resurfaced recently with the Totnes and Bristol pound and bartering economies in Greece and other austerity hit areas. They saw the benefits of keeping resources local as it then had further benefits of the community as a whole, this is echoed in the ideas of today’s local currencies as they recognise that money spent in supermarkets just goes to shareholders who can be based anywhere.

Owenite socialism also furthered the rights of women and he believed that the traditional tasks undertaken by women such as child rearing, cooking and washing should be transferred to the community to deal with as this would then share the burden as well as allowing everyone to undertake other work within the community. This idea would also strengthen communities and build solidarity and community cohesion as it would mean that more meaningful interaction between people would happen. This solidarity and interaction is important today more than ever, as we see people feeling very isolated and unsupported due to 30 years of Neo Liberalism and individualism crushing communities and people, as it pits them against each other through it’s emphasis on competition over cooperation and solidarity.

Owens influence can be felt the most today through the cooperative movement, as his cooperative store provided the inspiration for the cooperative movement of the Rochdale pioneers which has turned into a massive worldwide movement today. Cooperatives exist in all spheres of life and offer a different model of doing business.

Also Owen promoted a version of socialism which now has more links to anarchism than other forms of Socialism which focused on the state delivering services through nationalisation through a professional class, rather than a model of society whereby people self governed through cooperative communities. The idea of self government is very current as new communication technologies now enable more participation and models such as peer 2 peer are being promoted as models that could be utilised to organise society. Also the idea of self government has led to the development of systems such as consensus decision making that allow people to participate in decision making processes in a more direct manner.

More Information:

New World Encyclopaedia entry on Robert Owen

Website dedicated to Robert Owen

New Lanark World Heritage site

Article about Robert Owen the role of education

Cooperative College on Robert Owen’s Influence

Robert Owen & Utopian Socialism in New Harmony Indiana (Heaven on Earth)

Robert Owen & the Cooperative movement

References:

24. Robert Owen, Address to the Inhabitants of New Lanark, 1816.

25. Alfred Russell Wallace, Studies Scientific and Social, 1900.

26. Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Men, 1790.

27. Thomas Spence, Rights of Infants, 1797

28. Quoted in Barbara Taylor, Eve and the New Jerusalem: Socialism and feminism in the nineteenth century, 1983, p 150.

29. Letter from William Thompson to Anna Wheeler, 1825, quoted in Barbara Taylor, p ix

30. Barbara Taylor, pp 238-260.

31. Although it was not the first co-operative store; one was set up by the Weavers’ Society at Fenwick in Ayrshire as early as 1769.

32. Common Sense, 11 December 1830.

33. The full text of the Laws and Objects of the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, 1844, is available at www. archive. co-op. ac. uk/pioneers.

34. George Jacob Holyoake, History of Co-operation, 1875, rev ed 1905, chapters 15 and 16. See also George Jacob Holyoake, Self-help by the People: the history of the Rochdale pioneers, 1858, tenth edition 1892.