This is an on-going serialisation we are doing of a great little book called, ‘A history of community asset ownership’ by Steve Wyler who has kindly agreed for us to reprint his book on our website. We think a much better title for the book would be ‘The common peoples history’. We at Permanent Culture Now were going to do a very similar take on History that Steve has done with his book, so when we saw it we were like that’s great someone has already done the hard work. So we are expanding the work by adding our views as to why this history is relevant for today, drawing parallels with then and now and taking from it inspiration for building a more permanent culture.

A common peoples history of the UK part 6: Communities built by working people

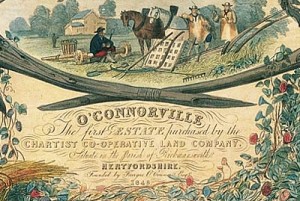

William Thompson, economist and advocate for feminism, believed that finance for co-operative communities would need to come from the working classes themselves, and they should have full ownership of their assets. Such ideas were drawn on by early trade unionists, and in the 1840s in the Potteries, and in the Sheffield steelworks, trade unions raised money from working people, to establish rural communities in England and in America. The greatest experiment of this kind was undertaken by the Chartist Feargus O’Connor, who founded five working class communities from 1846 to 1848, all with investment drawn from working people themselves. He set up the Chartist Land Company as well as a Land and Labour Bank, and 70,000 working people from the slums of the industrial cities raised nearly £100,000. This visionary scheme was tragically defeated by a lack of capital, an over-optimistic business plan, attacks by a hostile press, attempts to discredit the concept by commissioners of the hated Poor Law, and refusal of Parliament to allow the company legal status.

William Thompson

William Thompson, an Irish economist, political writer, and supporter of female emancipation, was one of the first utopian socialists to believe in the ability of the working class to create its own future. Thompson did not share Robert Owen’s faith that wealthy industrialists would provide capital for the new communities, and believed there was greater potential if working people themselves were to finance their own schemes. Thompson also believed in the necessity of the workers in any co-operative community having security of ownership of the community’s land and capital property. In 1830 Thompson published Practical Directions for the Speedy and Economical Establishment of Communities, on the principles of Mutual Cooperation, United Possessions and Equality of Exertions and of the Means of Enjoyment, in which he remarked:

William Thompson, an Irish economist, political writer, and supporter of female emancipation, was one of the first utopian socialists to believe in the ability of the working class to create its own future. Thompson did not share Robert Owen’s faith that wealthy industrialists would provide capital for the new communities, and believed there was greater potential if working people themselves were to finance their own schemes. Thompson also believed in the necessity of the workers in any co-operative community having security of ownership of the community’s land and capital property. In 1830 Thompson published Practical Directions for the Speedy and Economical Establishment of Communities, on the principles of Mutual Cooperation, United Possessions and Equality of Exertions and of the Means of Enjoyment, in which he remarked:

If done without any aid from the rich and idle, how animating to the industrious classes! – to the rich, the selfish, what a humiliating reproach!

In the same work he defined community as follows:

An association of persons, in sufficient numbers, and living on a space of land of sufficient extent to supply by their own exertions all of each other’s wants.

Community denotes common exertion and common benefit, common exertion according to the capabilities of each individual directed in the way most conducive to the common good, and common benefit according to the varying states and wants of each individual so as to produce as nearly as our best directed efforts can accomplish, equal happiness to all.

He hoped his instructions would make the establishment of co-operative communities as easy as for that of ‘any ordinary manufacture’. He also believed that communities would provide markets for each other, and that commerce would flourish as a result, with consequences entirely beneficial to society:

The system of Co-operative Industry accomplishes this, not by the vain search after foreign markets throughout the globe, no sooner found than over-stocked and glutted by the restless competition of the starving producers, but by the voluntary union of the industrious or productive classes, in such numbers as to afford a market to each other, by working together for each other, for the mutual supply, directly by themselves, of all their most indispensable wants, in the way of food, clothing, dwelling, and furniture.

Trade union communities

Several early trade unions attempted to establish communities where working people could live in prosperity and dignity, emancipated from the industrial slums – drawing on their own financial resources rather than going cap in hand to the state or to wealthy philanthropists.

In 1844 William Evans, who ran a newsagent’s shop in Shelton where he sold works by Wollstonecraft, Rousseau and Emerson, proposed to the newly formed Trades Union of Operative Potters that they throw their financial resources into a Joint Stock Emigration Company, to establish a model community in Illinois. He aimed to persuade 5,000 potters to buy a £1 share in the scheme, paying a shilling a week, producing a working capital of £5,000. By October 1844 all the potters’ lodges had voted in favour of the scheme, and subscriptions were collected. Emigrants were to be chosen by ballot when subscriptions reached each successive £50 level. They would arrive to find a cabin built for them, five acres of land broken and sowed with wheat and corn, and fifteen acres awaiting cultivation.

Wisconsin

This proved no hollow promise. The Union purchased land in Wisconsin and settled 134 individuals on 1,600 acres. Unfortunately, back in the Potteries, the unity of the pottery workers fell apart when a rival union was established. There was also discord in Wisconsin about equitable allocation of the land, which impeded the process of legalising the potters’ possession of the land. The immigrants complained of the heat, the water, the Indians, and the sandy soil. In June 1850 a meeting of settlers in Fort Winnebago raised charges of misrepresentation, corruption and incompetence. By January 1851 the Emigration Society was abandoned, and the trade union movement in the Potteries was set back many years. Elsewhere in Sheffield around 1848 other trades unions took up the idea of land colonies. The Edge Tool Grinders acquired a farm of sixty-eight acres at Wincobank ‘with a view to employing their surplus hands’, and the File Hardeners acquired a similar farm elsewhere. The Brittannia Metal Smiths established an eleven-acre farm at Gleadless Common Side, employing a manager and a dozen men who supplied a shop which sold the produce at market prices. Employees were paid 14s a week with 6d for each dependent child. (35)

The Chartist Land Plan

Just off junction 17 on the M25 on the outskirts of London, a quiet country lane leads to the village of Heronsgate with its imposing houses, immaculate lawns, expensive cars. But here and there within the spacious gardens lie small cottages, and the narrow lanes, designed for carts rather than cars, are named not after poets or war heroes or local councillors, but commemorate rather a series of industrial towns: Halifax, Nottingham, Bradford, and Stockport. For this was once O’Connorville, a community designed and built by working people for themselves, a memorial to the aspirations of mid nineteenth-century Chartism. (36)

Universal Suffrage

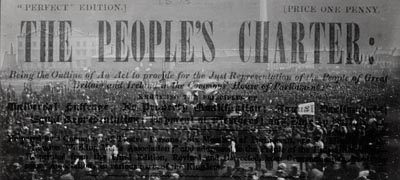

In 1838, and again in 1842, the Chartists had drawn up petitions calling for universal suffrage and annual elections, as a means of securing political power for all people rather than merely the privileged minority. They had travelled to town and village, collecting signatures. In Yorkshire when town meetings were banned they met by torchlight at  night on the moors, and at last the petitions, bearing millions of signatures, were carried with ceremony to Parliament. Twice the petitions were presented, and twice they were dismissed.

night on the moors, and at last the petitions, bearing millions of signatures, were carried with ceremony to Parliament. Twice the petitions were presented, and twice they were dismissed.

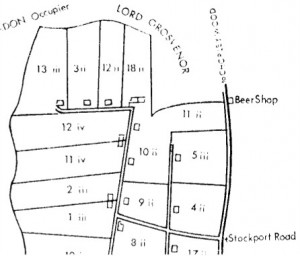

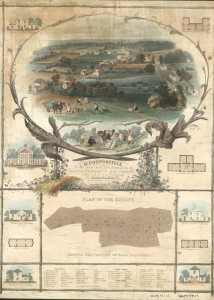

Feargus O’Connor, leader of the radical wing of the Chartist movement, came up with a plan to settle large numbers of working people on the land, each man holding property with an annual rental value of at least forty shillings, sufficient to qualify for a county vote. The aim was simple: when enough working people had obtained property qualifications, the people would be able to vote themselves the reforms which those in power had denied them. O’Connor was editor of the Northern Star and in April and May 1843 his newspaper ran a series of letters (written by himself) addressed to the ‘producers of wealth’, and suggesting that 20,000 acres could support 5,000 families, with four acres per family, in forty estates, each with its community centre, school, library and hospital. Subsequently he published a booklet, ‘A Practical Work on the Management of Small Farms.'(37)

Working people need to invest

Investment, he believed, would have to come from working people themselves. In 1845 O’Connor proposed that a company be formed and capital of £5,000 be raised from two thousand shares bought by working people for £2.10s each. This would allow 120 acres of good land to be brought at the current price of £18.15s an acre, providing sixty cultivators, selected by lot, with two acres each and £2,250 to buy cottages and stock. The allotments would be let by the company to the members in perpetuity at £5 a year (providing total rental income to the company of £300 a year). By selling twenty years of the rental income the company could raise a further £6,000, which would buy land for 72 families. Their rent would be capitalised in the same way and would buy land for 86 families, and so on.

Investment, he believed, would have to come from working people themselves. In 1845 O’Connor proposed that a company be formed and capital of £5,000 be raised from two thousand shares bought by working people for £2.10s each. This would allow 120 acres of good land to be brought at the current price of £18.15s an acre, providing sixty cultivators, selected by lot, with two acres each and £2,250 to buy cottages and stock. The allotments would be let by the company to the members in perpetuity at £5 a year (providing total rental income to the company of £300 a year). By selling twenty years of the rental income the company could raise a further £6,000, which would buy land for 72 families. Their rent would be capitalised in the same way and would buy land for 86 families, and so on.

Private property?

O’Connor travelled to France and Belgium and met socialist and communist leaders, including Marx and Engels. They were vehemently opposed, regarding private land ownership as the basis of opposition to change in society. O’Connor was not discouraged, remaining firm in his belief that by owning a cottage and a piece of land, people would achieve fulfilment, independence and liberty. O’Connor claimed that his plan would give everyone a chance to work for himself, would solve the problems of criminal law, dispense with many of the burdens of government and a standing army, and provide sanitary improvements and educational aid. In the Northern Star on 12th August 1848 he also claimed that the plan would reduce the suppression of wages of the industrial poor: ‘With my operations I will thin the artificial labour market by employing thousands who are now destitute, and constituting an idle reserve to enable capitalists to live and make fortunes upon reductions of wages.’ O’Connor insisted that he intended no socialism (on the Owenite model) nor partnership with the state. Ownership and control were always to reside with the individual, and O’Connor described himself as an ‘elevator’ not a ‘leveller’.

Land plan office

The Land Plan office was set up at 83 Dean Street in Soho. The legal form of the new company was the first obstacle. Charitable registration was impossible because of the Plan’s commercial aspects. The Registrar of Friendly Societies ruled that the company was not a type of savings scheme and was therefore ineligible.  The remaining options were to establish a joint stock company (which required prescribed forms of governance and account keeping), or by Act of Parliament apply for a royal charter, available for non-profit-making benevolent activities or for single purposes such as building a railway. All were expensive (the cost of a private Act of Parliament if uncontested was about £2,500) and none were entirely suitable. Initially O’Connor opted for the joint stock route, and approached the Registrar of Joint Stock Companies, achieving provisional registration as a joint stock company. The company was originally called the Chartist Land Company, then the Chartist Co-operative Land Company, and finally the National Land Company.

The remaining options were to establish a joint stock company (which required prescribed forms of governance and account keeping), or by Act of Parliament apply for a royal charter, available for non-profit-making benevolent activities or for single purposes such as building a railway. All were expensive (the cost of a private Act of Parliament if uncontested was about £2,500) and none were entirely suitable. Initially O’Connor opted for the joint stock route, and approached the Registrar of Joint Stock Companies, achieving provisional registration as a joint stock company. The company was originally called the Chartist Land Company, then the Chartist Co-operative Land Company, and finally the National Land Company.

Freeholds

Working people asked why they could not save to buy the freehold on their allotment. So in August 1846 O’Connor proposed to found a Land Bank where members could deposit money at 4% interest, and save towards the £250 purchase cost of their allotment. Deposits would progressively reduce an allottee’s rent. A levy of 3d per share per annum was made to cover expenses of the bank, arrangements of the company, and directors wages, and in January 1847 the Land and Labour Bank went into operation.

Working people asked why they could not save to buy the freehold on their allotment. So in August 1846 O’Connor proposed to found a Land Bank where members could deposit money at 4% interest, and save towards the £250 purchase cost of their allotment. Deposits would progressively reduce an allottee’s rent. A levy of 3d per share per annum was made to cover expenses of the bank, arrangements of the company, and directors wages, and in January 1847 the Land and Labour Bank went into operation.

The Land Plan was widely promoted and Chartist branches across the country collected 3d or 6d a head towards shares. By April 1846, 1,487 people had paid in full, enough to establish the first settlement, so O’Connor and his colleagues started to travel in search of land. In September 1846 he visited Devon but was not impressed, calling it the ‘land of Parsons, sour cider, and low wages.’ He settled on a piece of farmland outside Rickmansworth, and named it O’Connorville.

Model Cottages

The model cottages at O’Connorville had three rooms: a sitting room, kitchen, bedroom, and next to them outhouses for a cow, pony, cart, wash-house, dairy, wood, fowls, and pigsties. The company provided equipment, farm stock, manure, and fruit trees. O’Connor was determined that quality should be high and the cottages were roomy, well lit, with oak plank floors and good cast iron grates. As the town was being built, working people holding shares would turn up from all over England, finger the seasoned oak, and exclaim ‘Eh! But that’s rare stuff!’

The model cottages at O’Connorville had three rooms: a sitting room, kitchen, bedroom, and next to them outhouses for a cow, pony, cart, wash-house, dairy, wood, fowls, and pigsties. The company provided equipment, farm stock, manure, and fruit trees. O’Connor was determined that quality should be high and the cottages were roomy, well lit, with oak plank floors and good cast iron grates. As the town was being built, working people holding shares would turn up from all over England, finger the seasoned oak, and exclaim ‘Eh! But that’s rare stuff!’

The first settlers

A ballot was held to select the first thirty five settlers, and they arrived on 1st May 1847. It was, according to O’Connor, ‘England’s “May Day”‘, and a band struck up the tune ‘See the conquering heroes come’. At the official opening on 17th August 1847 O’Connor stood on a platform jubilantly waving a giant cabbage. In 1847 O’Connor stood for election to Parliament in a Nottingham by-election. In a campaign speech O’Connor described the case of Charlie Tawes, an allottee who had come from Radford to O’Connorville. Charlie had been shut up in a ‘Whig bastille’ (a workhouse), separated from his wife and children.

Now he had been reunited with them and raised to independence. Now he had four pigs in his sty (tremendous cheering). Would he have ever got them by sticking in Radford workhouse? If the government would put half the money spent on building workhouses into buying land for poor men, it would destroy the new Poor Law system.

O’Connor won a surprise victory. Across the country working people rejoiced. In Barnsley candles were lit in every working class window and the Chartist flag of green and pink hung over the streets.

A project develops

Over the next two years, working people continued to buy shares and money poured in. By the end of 1847 O’Connor was able to claim that over 60,000 members were holding 180,000 shares, and £90,000 of capital had been accumulated. Further settlements were built at Lowbands, Minster Lovell, Snigs End, and Great Dodford. Education was always a core objective: ‘The mind has not been forgotten, as each house is fitted up with a neat and elegant library.’ Schools were built and schoolmasters appointed, employed by the Land Company. The allottees represented a cross-section of the mid-nineteenth century working classes. Former occupations included:

Over the next two years, working people continued to buy shares and money poured in. By the end of 1847 O’Connor was able to claim that over 60,000 members were holding 180,000 shares, and £90,000 of capital had been accumulated. Further settlements were built at Lowbands, Minster Lovell, Snigs End, and Great Dodford. Education was always a core objective: ‘The mind has not been forgotten, as each house is fitted up with a neat and elegant library.’ Schools were built and schoolmasters appointed, employed by the Land Company. The allottees represented a cross-section of the mid-nineteenth century working classes. Former occupations included:

Coalminer, weaver, labourer, calico printer, shoemaker, limeburner, block printer, stockinger, baker, woolcomber, innkeeper, smith, tailor, stonecutter, cabinetmaker, joiner, potter, cordwainer, mason, grocer, piecer, moulder, nailer, victualler, postman, skinner, butcher, embroiderer, farmer, hatter, spinner, milkman, servant, gardener, lacemaker, overlooker, warehousemen, tinman, clerk, thatcher, plumber, painter, plasterer, mechanic, clothier, fustian cutter, grinder, bricklayer, trunkmaker, seamstress, warper, turner, carpenter, slater, schoolmistress, cotton band maker.

Life was hard

Life in the new settlements was difficult: the urban settlers were unskilled in rural trades, and often arrived malnourished and in poor health. Nevertheless, initial enthusiasm was high and by 1848 some of the allotments were, literally, bearing fruit. One claimed to have 700 fruit-bearing trees: apples, pears, gooseberries and currants.

Attempts were made to find customers for produce. At Great Dodford the settlers cultivated strawberries and made jam for sale in markets in Bromsgrove and Birmingham. At Lowbands and Snigs End market gardens were developed to supply Gloucester. At O’Connorville some residents became cobblers and carpenters, providing services to the agricultural community. Outbuildings were sometimes converted into small workshops, and at Great Dodford wives and daughters started making bonnets. Some allottees demonstrated a sound business sense, co-operating to buy coal and groceries at wholesale prices. But O’Connor was falling under personal strain. Like many a modern community activist he found himself doing too much of everything, describing himself as ‘bailiff, contractor, architect, engineer, surveyor, farmer, dungmaker, cow and pig jobber, milkman, horse jobber and Member of Parliament.’ He started drinking heavily.

Challenges

The uncertainty of the company’s legal status was a great burden. In an attempt to meet the regulations for the deed of registration, the company directors were advised (wrongly it seems) that they needed to collect 40,000 signatures. The company’s representatives travelled from town to town in a weary and expensive attempt to achieve this. National and regional newspapers began to attack the company’s business methods, pointing out with sanctimonious glee that while incorporation remained unresolved, the legal rights of working people in the settlements were uncertain. This created a crisis of confidence. Receipts dropped quickly towards the end of 1847 and some of the lucky winners in the ballots promptly sold their allotments, for amounts between £70 and £120. O’Connor found it hard to hold his tongue and addressed the editor of one national paper as ‘You unmitigated ass! You sainted fowl! You canonised ape!’

The uncertainty of the company’s legal status was a great burden. In an attempt to meet the regulations for the deed of registration, the company directors were advised (wrongly it seems) that they needed to collect 40,000 signatures. The company’s representatives travelled from town to town in a weary and expensive attempt to achieve this. National and regional newspapers began to attack the company’s business methods, pointing out with sanctimonious glee that while incorporation remained unresolved, the legal rights of working people in the settlements were uncertain. This created a crisis of confidence. Receipts dropped quickly towards the end of 1847 and some of the lucky winners in the ballots promptly sold their allotments, for amounts between £70 and £120. O’Connor found it hard to hold his tongue and addressed the editor of one national paper as ‘You unmitigated ass! You sainted fowl! You canonised ape!’

Petitions

In February 1848 O’Connor, desperate to achieve legal status, presented a petition to Parliament to legalise the company through Act of Parliament, and the Bill received a first reading. It was not immediately rejected, probably because the government did not want to be held responsible for dashing the hopes of so many working people. A date for a second reading was appointed and a Parliamentary investigation began. Complaints started to surface from within the company. Meetings of Directors and dissident representatives were called, to which O’Connor was not invited, and he used the columns of the Northern Star to vent his frustration and anger.

Poor law

The enquiry took evidence from a Poor Law specialist, who pointed out that tenants would be eligible for poor relief by virtue of length of residence and level of rent they paid, and this meant that if the allotments failed and the tenants threw themselves on the parish for relief, rural parishes would be forced to levy a massive increase in poor rates and this would suddenly reduce to nothing the value of every property in the parish. His conclusion was that the settlements were not sustainable, and therefore that they were likely to lead to ‘serious and sudden burthens upon the poor’s rates of those parishes in which they acquire land.’ He noted that the allottees were not yet paying rent, that manure provided in the first year had been used up and not replaced, that some of the settlers had already fled the land.

O’Connor defends

O’Connor replied that the settlements were viable, and that he had provided ‘a market, better than the gin-palace or the beer-shop, for those who had small savings to carry to the labour field.’ One of the committee members travelled to Snigs End and Lowbands to see for himself. He was surprised at the high standard of building and cultivation on Lowbands. Wheat and potatoes, he reported, were as good as those of any farmers. There were accusations of financial mismanagement, even suggestions that O’Connor had been lining his own pockets by tricking the poor. Clutching bundles of paper, O’Connor pulled out records and accounts. A government accountant claimed they were unintelligible, so O’Conner took him to Great Dodford and showed him more piles of papers. Patiently the accountant examined them all. His conclusion was a vindication of O’Connor: ‘I am thoroughly satisfied, not only that the whole of the money has been honourably appropriated and is fully accounted for, but also that several thousand pounds more of Mr O’Connor’s own funds have been applied in furtherance of the views of the National Land Company.’

More attacks

So far O’Connor was standing his ground, but there was worse to come. A government barrister, Edward Lawes, asserted that the company was established for the purpose of an illegal lottery, where many paid but only a few would gain. Subscriptions from 70,000 (of whom about half had fully paid up) had been necessary to locate 250 people in the new villages. A single subscription could never suffice because the cost per location was between £200 and £300. Total subscriptions amounted to £91,000. £35,000 had been spent on buying land, £50,000 on forming and building estates, £4,000 on expenses of management. Cash assets were £7,000 but there were debts to the Land bank of £6,800 and at least £3,000 was owing to O’Connor. So there was no money to build more estates, unless the reproductive principle, whereby rental income would be capitalised to raise the investment for the next estate, and so on, could be proved viable.

Sustainable?

Lawes claimed it could not. As the number of subscribers was 70,000, and the cost per allotment £300, the sum needed was £21m. Fully paid up shares from the 70,000 subscribers would bring in capital of £273,000. The government accountants showed that by mortgaging and re-mortgaging, the original capital could grow to a total of £819,000. This would locate 2,730 people, but leave 67,270 members unprovided for. Moreover, the scheme would take longer to realise its benefits than the lives of its members: even if all the capital were mortgaged and each new estate were bought and built within a year, the company would take 75 years to house its members. On 30th July the Committee delivered its verdict to the House of Commons. The company in its present form was illegal, and accounts were imperfectly kept. The large number of people involved, all of whom had acted in good faith, should be allowed to wind up the undertaking and relieve themselves of the penalties to which they had subjected themselves. Finally, careful to give the appearance that the government was critical only of the methods, and not of the social objectives of the company, the Committee stated that ‘it should be left entirely open to the parties concerned to propose to Parliament any new measure for carrying out the expectations and objects of the promoters of the company.’

Defeat

This was a crushing defeat. In the Northern Star O’Connor attempted to present the verdict in the best possible light. He implied that contributions from the poor alone were inadequate to capitalise such projects, pointing out (with justice) that subsidy on a large scale was provided by the government of the day for other projects in the national interest, such as railway and mining schemes. However, the spirit of common enterprise eroded rapidly, and now everyone looked only to their own interests. The tenants were determined to acquire a title deed and not to pay rent, the unallotted members wanted no-one to get a penny before the final dividend and demanded that back rent be paid, the directors and staff wanted to extricate themselves and leave O’Connor to carry the full responsibility for failure, and O’Connor wanted payment of his own expenses.

This was a crushing defeat. In the Northern Star O’Connor attempted to present the verdict in the best possible light. He implied that contributions from the poor alone were inadequate to capitalise such projects, pointing out (with justice) that subsidy on a large scale was provided by the government of the day for other projects in the national interest, such as railway and mining schemes. However, the spirit of common enterprise eroded rapidly, and now everyone looked only to their own interests. The tenants were determined to acquire a title deed and not to pay rent, the unallotted members wanted no-one to get a penny before the final dividend and demanded that back rent be paid, the directors and staff wanted to extricate themselves and leave O’Connor to carry the full responsibility for failure, and O’Connor wanted payment of his own expenses.

Relationships strained

Relations between O’Connor and the allottees became tense. Some who refused to pay rent were letting their houses and land to others and drawing good rent for them, so O’Connor threatened to sell the estates, and dissident groups emerged among the tenants. Despite everything, during 1849 the Company pursued attempts to register the company under the Joint Stock Companies Act. Building continued at Great Dodford, and sowing and planting at the other estates.

But O’Connor was under attack from all sides and even within the Chartist movement he was isolated. In April 1848 the last great Chartist petition had been presented to Parliament, in a wagon drawn by four horses from O’Connor’s estate at Snigs End, trimmed with red, green and white streamers. But when the petition had been examined it was found to contain far fewer signatures than claimed. O’Connor had become frantic and abusive and fled the chamber. Many of the national Chartist leaders attacked O’Connor, claiming he was ruining their cause by his extreme views and erratic behaviour. Others in the co-operative movement complained that the Land Plan had diverted the energies and resources of working people away from their efforts. (38)

Takes its toll

O’Connor was now suffering badly. His red hair began to turn white and he was said to be drinking heavily. He was losing control and in August 1849 he wrote a bizarre letter to Queen Victoria beginning ‘Well Beloved Cousin’, and signing himself as ‘Your Majesty’s Cousin, Feargus, Rex, by the Grace of the People.’ For a while O’Connor rallied; he went on a speaking tour of the Scottish branches and was received with acclaim. Support also came from the pioneer sociologist Harriet Martineau, who wrote two open letters on the capabilities of two and a quarter acres of land to support her household of five, with the labour of one man from the workhouse. But nothing now could save the scheme. In June 1850 the courts rejected the attempts to register the company. In July a petition was made to wind up the company, and in 1851 it was finally closed down.

O’Connor struggles

In 1852 O’Connor assaulted a policeman after a row at the Lyceum Theatre and spent seven days in prison. News began to circulate that he was neglected and in need, and working people responded quickly and generously: a fund was started in March, and allottees and members from across the country subscribed what they could.

But in June O’Connor was taken to a clinic for the insane at Chiswick. He considered himself a state prisoner, and regarded his confinement with ‘grave pride.’ In 1854 the first signs of epilepsy appeared, and in 1855 his sister removed him from the clinic to her home. On 30th August he died and on 10th September large crowds followed the coffin to Kensal Green cemetery. The epitaph reads:

Reader, pause,

thou treadest on

the grave of a patriot.

While philanthropy

is a virtue, and

patriotism not a crime,

will the name of

O’CONNOR

be admired and this

monument respected.

What happened next

By 1858 at O’Connorville, soon to be renamed Heronsgate, only three of the original settlers were left. Because the estate was close to London, the houses were bought up by well-off people who enjoyed the privacy given by the large grounds about the house. Not much is left in Heronsgate of its radical past, although the local pub bears the name ‘The Land of Liberty, Peace and Plenty.’ After a while some of the original Chartist cottages in the other settlements were also replaced with larger houses, although quite a few have survived and one at Great Dodford is maintained by the National Trust in its original condition. Soon the memories of the original settlers had passed into local folklore, and for years afterwards the story was told of the man, arriving at Charterville (Minster Lovell) from the northern slums, who, it was said, had never seen a pig before and chastised it for noisiness.

O’Connor has not been treated kindly by historians. For some the fact that he was an outspoken Irishman was sufficient to condemn him as a demagogue. Early accounts of Chartism were written by more moderate Chartists, who feared that O’Connor’s radicalism jeopardised public acceptance of their cause. They criticised his community experiments, believing that they were a distraction from the primary goal of universal suffrage, which they considered to be the only path to justice and prosperity. Today, in the knowledge that the right to vote has not, on its own, produced these universal benefits, O’Connor’s vision has more resonance than ever.

William Thompson differed from Robert Owen as he believed that working class people should fund there own schemes to become self sufficient and he believed that people needed to own there own land in order to do this. This model can be seen as a precursor to the Housing cooperatives that we see operating today in many parts of the world, where people who are members of the cooperative own the property collectively. He also saw that people needed to have enough land to meet their own needs, an issue that remains to this day, as very few people now have access to land to meet their needs, which means they are dependent upon others for their basic needs. This idea can be seen as crucial to the modern day ideas of the commons, where it is argued that resources that meet basic needs should be held in common by all and administered on the basis of human well being.

Thompson also believed that a community should de structured so that people could contribute in a way which is linked to their capabilities with the aim of equal happiness for all. This is a very important idea as it promotes collective action and equality based on ability, not on ones ability to earn money. These ideas would go on to influence anarchist ideas based on mutual aid and cooperation. This is fundamentally a different dynamic to that of capitalism which pits people against each other and definitely does not distribute resources based on the aim of equal happiness, in fact resources are distributed very unequally. We would argue that this basic philosophy is still very much relevant to day, if not more so in a time where more and more people are excluded from society because of illness or lack of modern day skills, particularly when the overriding cynical view seems to be that if you do not financially contribute (sic) towards the economy then you are a burden on society.

Trade union communities may not exist in a physical space, yet they are still an important way of organising to build power in society, although in the UK its seems that many trade unions have become managers of change for the capitalist class, rather than defenders of their members rights. That said Trade Unions are still the organisations that have the capacity to pull together large groups of people, though we would be more inclined to promote the syndicalist type of trade union that organisations such as the International Workers of the World (IWW) that are organised from the bottom up, organise across the working classes in all sectors and believe in workers having control over the means of production.

The Chartists called for Universal suffrage that is that all people can participate in the political process and for this to be held annually. These demands are still very much relevant, as not all countries have a democratic process and those that do are often undemocratic once you scratch beneath the surface. For example in the UK you only vote once every 4 or 5 years, then there is no accountability or recall in place, so parties can say what they want before they get into power then do as they wish, there should be some sort of contractual obligation and accountability in this process. In the UK the first past the post electoral system, pretty much excludes any parties with a semblance of radical politics from gaining any position of power.We would argue for a much more democratic system that involves people in a far more inclusive way, which reflects the interests of the 99%, where by representatives are accountable to the people they serve. Parliamentary democracy in many countries offers no real options as all parties are tied into the Neo Liberal model, in the UK and the US all main parties basically agree on the Neo Liberal model, which has now been shown to be fundamentally flawed as a result of the debt crisis.

Universal suffrage is not the issue now, systemic change is the real demand because even if we can all vote, we have very little to vote for and there is no accountability to electorate. We need to rule ourselves, not to be ruled over by a plutocratic (Government by the wealthy) corptocracy (Government of, by, and for multinational corporations). The issue for people in countries with universal suffrage is now the political system as it interacts with the public, now we have been given the right to vote, the way that is implemented is in fact completely dis-empowering and it is this that needs to change. Also agree with there call for more regular elections as this would stop groups who are acting illegitimately from causing major damage, although in a better political system with built in accountability this would be less of an issue.

O’Connor was quite astute to the role of the poor in the dynamics of capitalism and his analysis stands today. He viewed the destitute and poor as a tool for capitalists to drive down wages and he believed that by making the poor self sufficient through giving them a house and land would then stop the suppression of wages. O’Connor was very much a believer in private ownership as the way of changing society and was interested in setting up structures such as the setting up of the Chartist Land Company to develop this model of society. He clashed with other radicals on this point as he was somewhat a reformer and actor within the existing political and economic system. We would take issue with the reformist stance that he promoted mainly due to the fact that there is now such massive inequality in the world, that there has to be redistribution of wealth and resources in order to move to sustainable, fairer society.

The situation in O’Connor’s time would have been very different, as there was the possibility for the development of a more localised response to what was occurring and capitalism was still in it’s infancy as a dynamic so the potential for developing a new society was more possible. O’Connor should be admired for his successes in developing independent communities that improved the lot of poor people. If a comparison is to be made with today, I would highlight the attempts of people to create eco-village communities, as they are attempting to create a new model of living within the existing system, as the cooperative movement also attempts, but as good as this is, we would argue that you cannot divorce yourself completely from the existing unequal economic and political systems that disadvantage us all and it is those structures that need to be changed.

It could be argued that the failure to really address these social structures that the project was operating under made it very difficult for O’Connor to sustain and develop the project and if you look at the problems that beset them it was the legal issues (caused by government not recognising them as a legal entity), the potential burden on the parishes of the projects failing (again an issue of unequal resource distribution), then the ruling class also tried to discredit him through saying he was a thief and that the scheme was an illegal lottery as it could not sustain itself (which in reality did seem to be true). So the state and the ruling class of the time appeared to be making it very difficult for the projects to develop through there use of law and propaganda, as well as there being financial pressures. If the Chartists had been more revolutionary then maybe some of these issues would not have been issues, as the state would not represent the needs of the ruling class and the distribution of resources would be decided through a different process. Maybe levelling was needed, not the escalating that O’Connor saw as the route to social change.

More information

William Thompson (1775 – 1833) – Introduction to the writings of William Thompso

Dramatisation of the trial of the Chartists at Shire Hall

Potters examiner Wisconsin or bust

Lots more information on the chartists movement

Spirit of the Chartists carries on today

Bristol Radical History Group on the Chartists

A short animation telling the story of Chartism and the struggle for working men to receive the vote.

The Chartist Anthem is a song sung by Chumbawamba. The song dates from the 1840’s and is about the campaign by working men for the vote.

Talk by John Foster on People’s Charter

Following on the the Great People’s Charter of 1839 lead by the Chartists. Chartism was possibly the first mass working class labour movement in the world.

References:

35. W H G Armytage, Heavens Below: 88 Development Trusts Association Utopian Experiments in England 1560-1960, 1961, pp. 246 and 254-258.

36. See Alice Mary Hadfield, The Chartist Land Company, 1970, reprinted 2000.

37. Feargus O’Connor, A Practical Work on the Management of Small Farms, 1843.

38. For example George Jacob Holyoake, Self-help by the People: the history of the Rochdale pioneers, tenth ed 1892: ‘We are bound to relate that the capital of the Store would have increased somewhat more rapidly, had not many of its members at that time been absorbed by the land company of Feargus O’Connor.’

The model cottages at O’Connorville seems to be a kind of mass production, maybe a sort of that idea that for everyone to be equal, everyone should live in the same kind of home.

Christopher Alexander on the contrary stresses that to make living communities every place, every house and every room needs to be unique, shaped accordingly to every individual’s deep personal feeling and character.

Equality cannot be shaped through similarity, it can only be created through shared pattern languages.

We, in our time, have a special responsibility to create new pattern languages, supporting a movement or network of global villages: http://wealthofthecommons.org/essay/commoning-patterns-and-patterns-commoning-short-sketch

Today’s information technology will go away:

“Villager, computers don’t build themselves, they don’t power themselves, they don’t mine the raw materials to make their own spare parts for themselves, and so on. They’re simply the final hurrah of the age of cheap abundant energy, and will go away as the immensely complex and energy-hungry infrastructure needed to support them becomes too costly to keep running. Thus I don’t think that the invention of computers is anything like a game-changer.” – John Michael Greer

The same way as computers will be gone, we will see a return of the village as the basic form of community:

“Ashley, I’d suggest a slight variation. Through most of history, the urban-civilization form of society supported itself on a foundation of decentralized villages; the latter is the basic form, the former an occasional blossoming, which runs its course and ends. Our current civilization, as I’ve argued in a couple of my books, is as brittle as it is precisely because it tried to replace the village system with factory farming powered by fossil fuels; as those run out, it’s not going to last — and then, as you suggest, we’ll be reverting to a stabler form.” – John Michael Greer

This is why I see GIVE, the Global Villages Movement, as the most important movement of the world today: http://www.globalvillages.info/wiki?GlobalVillages/GIVE

The cities will fade away, people will have to return to the basic form, the village. To create a network of villages, to be managed as commons, ruled by internationally but locally adapted pattern languages, is the future of humanity!