This is the first of a great series of 8 weekly lectures about modern life and the post modern condition by the great Rick Roderick the Bill Hicks of Philosophy. What is great about this series is that Rick delivers it such a great way that is very easy to understand, he makes difficult concepts clear and illustrates them in a interesting and engaging way. When I first found these lectures, I had to watch all of them one after another great and I urge you to do the same. Below the film is the transcript of the talk and a summary of the main points, but please watch the lectures first as they deliver a lot. Enjoy and raise a glass to Rick Roderick who unfortunately is no longer with us.

This is the first of a great series of 8 weekly lectures about modern life and the post modern condition by the great Rick Roderick the Bill Hicks of Philosophy. What is great about this series is that Rick delivers it such a great way that is very easy to understand, he makes difficult concepts clear and illustrates them in a interesting and engaging way. When I first found these lectures, I had to watch all of them one after another great and I urge you to do the same. Below the film is the transcript of the talk and a summary of the main points, but please watch the lectures first as they deliver a lot. Enjoy and raise a glass to Rick Roderick who unfortunately is no longer with us.

Summary of the lecture:

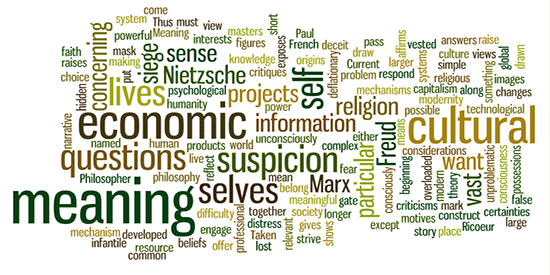

- Current professional philosophy is “deflationary” in that it gives no answers to our larger questions, in particular our questions concerning our selves, our projects, our questions concerning our own selves, our projects, our place in society and in the world.

- We have lost a vast resource of cultural meaning upon which we could draw to construct meaning for our lives. Meaning, in this large sense, can no longer be drawn unproblematic from religion. We have information, but not knowledge.

- We all strive to have a “theory” or narrative about our selves., we want to have a meaningful story about our lives that affirms our humanity. In short, we want them to mean something.

- The complex systems under which we live (economic, technological, global) have put the self”under siege”, overloaded with information and images that offer no meaning for us. We have difficulty making any sense out of our lives.

- Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche (the figures named the “masters of suspicion” by the French Philosopher Paul Ricoeur) developed powerful criticisms of out cultural mechanisms of meaning in particular religious meaning. Taken together, they raise the problem of “false consciousness”, the suspicion that our certainties and our beliefs are the products of hidden economic, psychological, and cultural motives.

- The reflect and respond to the vast changes in out views of what it means to be human that come along with modernity and the economic and cultural system of capitalism. Marx exposes religion as a mask for vested economic interests, Freud shows its origins in infantile distress and fear, and Nietzsche raises the suspicion that it is a mechanism of power and deceit. After them, no simple faith is possible.

- They are the common possessions of our culture and their critiques belong to us. We have no choice except to engage them either consciously or unconsciously. They are the gate through which any relevant modern view of the self must pass. Thus, they mark the beginning of these considerations of the self under siege.

Transcript

The course that I am about to present: “Philosophy in the 20th Century – The Self Under Siege” has been a difficult course for me to develop over the years, and it’s been a difficult subject matter for me because I have been trained in the classic tradition of philosophy, studied ancient philosophy, know many of the methods and taken all the required logic courses and so on. I have also done a lot of work in Continental Philosophy as well. It seems to me that the late 20th Century presents us with one great and overriding problem and that will be the focus of this course; and I had second thoughts about even calling it a course in philosophy because the most current philosophical attempts to understand both the self, society – our place in it and so on – have been what I will call “deflationary”.

The course that I am about to present: “Philosophy in the 20th Century – The Self Under Siege” has been a difficult course for me to develop over the years, and it’s been a difficult subject matter for me because I have been trained in the classic tradition of philosophy, studied ancient philosophy, know many of the methods and taken all the required logic courses and so on. I have also done a lot of work in Continental Philosophy as well. It seems to me that the late 20th Century presents us with one great and overriding problem and that will be the focus of this course; and I had second thoughts about even calling it a course in philosophy because the most current philosophical attempts to understand both the self, society – our place in it and so on – have been what I will call “deflationary”.

I will use for example… I will just mention an article by the philosopher Richard Rorty called “The World Well Lost“. This is the upshoot now remember of a tradition that is at least 2500 years old, and now that tradition is produced in tiny little articles – four, five page articles – in journals that are read by a number of people that’s a small enough number that if they were all in a boat and it sank, they would have no readership. And it could be a small boat, it wouldn’t need to be Lusitania, it could be a raft, perhaps. But in any case, Rorty in one of these journals wrote an article called “The World Well Lost” and developed a principle that I think has become widespread toward the end of the 20th Century, concerning philosophy’s role in informing us about ourself, or about the world.

The title itself indicates it: “The World Well Lost”; Rorty’s view is that any problem that has been around for 2500 years for which we still don’t have a solution, the right response by the contemporary philosopher is “I don’t care”. And the charm of Rorty’s answer is it’s so American. It’s deeply rooted in our culture, in both the anti-intellectualism of our culture, in our fear of eggheads and so on, and so in that sense it has a double significance. Positively it means that the work of intellectuals has always been separated off from the work of ordinary people. In other words, you have to be freed from the constraints of manual labour. When I was a dishwasher, I didn’t have a lot of time to do this. When I was a union organiser, I didn’t have a lot of time to do this. Any time I was involved in manual labour, I didn’t really have the time to do this intellectual work.

That separation, that fateful separation between intellectual and manual labour has been with philosophy throughout. It’s rather disappointing though to have that tradition – the great tradition of thinking in general – be reduced to a comment like “Well, gee… I don’t care. We haven’t figured it out” Similarly let me give you one more example of the profound results of recent contemporary analytic philosophy. The most widely accepted theory of truth is Tarski’s theory of truth. I won’t do it justice here but I will, I think, give you an account that fairly summarises its main insight.

Tarski’s theory of truth goes something like this. Tarski says the sentence “Snow is white” – and he puts “Snow is white” in quotation marks – is true, if and only if snow is white. I don’t expect anybody in the audience to gasp, if you follow me. This isn’t a theory of truth; this is the deflationary remark about how we use the word “true”, you follow me? It’s just… this is not the upshot of what we thought were the glowing and humanistic accounts that I appreciate to this day, developed by Socrates, Aristotle, all the way through Aquinas and so on, and in the late twentieth century what we get in area after area are these – what I will call – deflationary accounts. On the upside, these accounts don’t pretend to know much. I mean, that’s the upside for me. In other words, they are not overly grand.

And I have no idea what other courses The Teaching Company has been offering lately, except through the catalogue, and I don’t want to undermine any of them, but for example: the substantive attempt to defend God in an intellectual setting where philosophical argument is key has been doomed for so long that that won’t be our central attention, although we may mention that as we go by… go through today.

Well why do I start with these rather snotty remarks – if they are snotty – I mean, it may turn out that these deflationary things are all we do know: that snow is white if and only if it’s white, and that if we can’t tell whether we are free or determined after two thousand and something years, then the best attitude to take is “I don’t really give a damn” I mean, if that turns out to be the right view, we’ll leave ourselves with that.

But there are some problems – and this is going to be the heart of the course – about which a deflationary view is hard to take, and one is our view of ourselves as selves, our own self reflective view about what we are as human beings, what is our place in our society and in our world, and more importantly maybe, what is our place vis-a-vis our commitments; our stations in life, our roles as husbands, wives, fathers, and I guess today to be absolutely correct about everything, significant others, significant other others, dogs and cats, whatever. I mean, you know, I’ll just cover the whole gamut here to try to be contemporary. [cough].

These are questions about which it’s extremely deflationary to go “Oh yes, the self… ah, I haven’t got one”. I mean, that’s disappointing in a different kind of way. I mean, many of you say sentences that are true, without having a theory of truth, I hope. I mean, it routinely happens. It happens in pool halls; people say “I can make the 8″ and they make it, and you go “That’s true”. You don’t then ask for a theory of truth. Very few of you have a theory of structural grammar, or empirical grammar, but most of you don’t say sentences like “sclaglaglugglankgleeee”. You say sentences like “It’s raining today” and yet it would be kind of silly to ask you for a theory of grammar. And again, the self is a different story; with the self, the human subject.

I am not saying that you’ll tell your story – whatever your story happens to be – to just anyone. But it’s hard for me to imagine – and perhaps this difficulty in imagining it is just my difficulty in dealing with the world as it is today – it’s difficult for me to imagine anyone taking that kind of cavalier attitude about their view of themselves. And I would like to argue in a strong sense that every one of us has some kind of theory of what we are as a person.

Now, by that I don’t mean a really highly developed theory like in quantum mechanics or anything like that. I may only mean a narrative story. Something that connects – or attempts to connect – the various disconnected episodes in our lives. Something that gives us a reason to think that we are the same person we were yesterday in some important sense, even if that only means you still have the same drivers’ license. In some way we want to have a narrative about ourselves. We want them to mean something, in short.

And I don’t want to go off in this first lecture on a long, ah, exegetical set of remarks on this new phrase, which I am afraid is going to be just a part of pop psychology: “the politics of meaning”. I don’t have any idea what they are talking about, okay. I don’t know. This is not what I am talking about. What I am talking about is much more immediate, and it may in fact have political implications.

By that I mean… it may mean, that people can have refrigerators, nice cars, nice homes, nice children, and nice degrees, and you know… nice friends… and have absolutely no sense of who the hell they are… and be in utter despair. In fact, ah, that condition, on the account I will be giving will be structurally common. This is not a slam on any people who are personally in the audience today, or any people viewing me. It’s not a personal remark. It’s a structural condition. And so, therefore the title: “The Self Under Siege”.

And, ah, whether philosophy is the right discipline to look at this problem or not is unimportant to me, because in looking at it myself, I have been guided more by the problem, than by the discipline that I started out working in. I mean, when I look at a college curriculum and see how its divided – and we have committees that redivide them once a week, or once a month… once a year… I mean, I don’t give a damn what studies this or who talks about it, but that it’s part of the ongoing conversation of our species about itself… you know… who we are, seems to me to be very important, even if it is taught in the curriculum under the heading “Basket Weaving”. It’s an utterly, crucially important topic in my view.

The self under siege comes about in part – the sort of apocalyptic tone to the lectures – comes about in part because I really do believe that new factors; new social factors and others in the late 20th century have led to a kind of pressure on human beings, on selves… not on them as individuals; not as individuals, but on them anonymously. In fact the systems I have in mind are anonymous systems, and I’d like to characterise a few of those, and as I do so, I will be running through what I might call some of the pathologies of the 20th Century and see if there is any way that a conversation rooted in philosophy – in some sense, at least – could help us find our way about in it.

The most obvious one in the late 20th Century… and I thought about this in the hotel room this morning as I saw the arteries of the beltway running like human blood through a body into the city. And then I also thought about the follow thing, I think I mentioned at the end of my last lecture on Nietzsche, when I was discussing the postmodern condition, and that’s what I would call the information overload. And I’ll try to make this come alive with an example from a different culture.

Let’s take being a Tonkawa Indian in West Texas. They weren’t a very well known tribe, but they are from my home area so I will mention them. The Tonkawa Indian’s reservoirs for meaning – the best cultural anthropology work we have – were rich but a limited array of roles, stations, things to be, and so on, but they were rich and holistic. In other words, in that sense, there were an array of things you could choose to be, and there were a wide array you could choose not to be. Like Chief, you didn’t exactly choose to be that. But among this array, the decision paths were relatively simple. Relatively simple. And the information load you received in – the load of information; the number of images and so on that you saw, the number of things that actually touched your skin, impinged upon your perceptual apparatus – was quite limited.

Compare that situation to the 19th Century, and already we have human beings under considerably more pressure. Because from the late 19th and into the early 20th Century, many things come about that we don’t think about philosophically, but which shape our reflection not only in philosophy, but in everyday life. I mean, we walk into a B. Daltons as though there were always cheap paperbacks available to everyone. But that’s actually a quite recent development in the history of the world. We fill our universities with them as though they are some ancient treasure, and television is some degraded form of the present. And of course, that’s idiocy. Those cheap books have only been around very recently in the history of thinking. Television now has been around for about, you know, a third of that same time…

So the point I am driving at here is the incredible increase in information; the amount and the tonnes of information. This city itself: Washington D.C. is a good example. I think if you took all the information collected in the history of the world, between the dawn of humanity – earlier than the dead sea scrolls – back when, oh I don’t know, hell, maybe Steven Spielberg did it in Jurassic Park, back when dinosaurs dipped their tails in the mud, and whatever – all the marks, sensible marks left by us beings of whatever kind, I am almost certain that in the last eight years in Washington there is more information piled in four buildings than the whole previous informational load of the history of the human species.

To give you and example that may be more immediate, think of the JFK assassination. Is our problem there lack of complexity, lack of information? No! We know way too damn much about it. Way too much. There are too many possible assassins, too many secret plots, too many movies, too many books. And under this kind of complexity the self finds itself in a position where the array of choices of what to believe or not to believe become bewildering, utterly bewildering. Now this is about events like, you know, the assassination and so on but, you know, the more important beliefs are beliefs about ourselves become equally bewildering.

In the earlier phase of capitalism – the 18th and 19th Century – the average worker would change jobs in a lifetime – and I think this went on through the 40′s and 50′s – you’d change jobs once, maybe twice a lifetime. Now people change jobs seven or eight times in a lifetime. What I am pointing to here is that the self must find meaning now – however it finds it – in a system in which it seems to me objectively true that the complexity level has reached a point at which nobody… and this is not cartesian doubt, you know, this isn’t doubt brought on by an evil genie who makes me wrong to my clear mind.

No, we doubt in a different way now, we doubt that we could know enough about the big picture to even make sense. I mean that’s why, you know, one of the battle cries of these lectures will be to “just make sense”, because that will be very difficult to do. Because we will be doing it in a situation in which there is way too much to make sense about, and in a situation in which the complexity of the systems in which we try to make sense are way, way too complicated. Even our purest motives get caught up in these systems.

I’ll give you an example, and I don’t mean to have every environmentalist in the world burn my tapes, but let me give you an example of system complexity. Suppose America got behind recycling massively, and we began to recycle and become a very efficient society and we’d all be proud of each other, and I mean you know, nobody debates environmentalism anymore, right? Even McDonalds is an environmentalist now. I mean for God’s sakes, McDonalds… I mean, they are even for Martin Luther King now, I wish they were there a few years ago, but anyway that’s another point… not a happy one.

But no, suppose we became that environmentally conscious, well we’d all feel good, our society would be cleaner. What would be the outcome in the third world where the only things they have to sell us are cheap labour and things that we can’t ruin in this country? I don’t think it’s a long causal argument to see that an American renaissance in environment would be utterly disastrous for countries in the third world who have nothing to sell us but poisonous gunk. I mean, this is the bad news.

This is in a way the disappointing thing about even contemporary political attempts to make sense of the self. I mean, we hear politicians say “Oh well, there is no conflict between the environment and the economy”, and we go “Yeah, I guess there doesn’t have to be”. But to the extent we give it thought at all, it’s not within the context of these large, massively complex systems… about which believe me Bill Clinton, I think, clearly doesn’t know any more than any one in this room, in fact I think the judgement of the American people is he knows far less about most of these, and this certainly isn’t the time to make a didactic political argument to bring in the last bunch of hacks who also couldn’t deal with complexity, because the self under siege, part of what it’s about is the complexity of meaning.

Now this makes the world a double world in a way. The world is on the one hand as rationalised as it’s ever been. That means that down to its smallest detail we have chased what you might call – what I will call – “information”; what universities call “knowledge”. I don’t view it as knowledge, I am sorry. I look at it as information. That itself is a deflationary term. We have tonnes of that. It’s rational, we chase it down.

Now here is the paradox… is that a world filled with instrumental – what I will call instrumental – rationality, and by instrumental I will mean technical rationality; the kind that is measurable, quantifiable, that can be found in many sciences and in banking, accounting, and so on… advertising, the law, and so on. That this kind of technical reason produces a situation [in] which human beings don’t feel rational. And especially with a younger audience, and I think this is really true with the twenty or thirty somethings that are out there listening to me, ask around and see how many of your friends – if you think the self isn’t under siege in the late 20th Century – ask yourself how many of your friends are on twelve step programs to stop something. Ask yourselves, given the current use of the word “dysfunctional”, who is not?

I mean you know, this is to me the best sign that the self is under crisis. There is a twelve step program to stop eating; of course, if it succeeded utterly you would die. Twelve step programs to stop having sex, if that succeeded utterly the species would die. Twelve step programs to stop thinking are what we need next. Of course they have those already; they are called “network television”. That’s a twelve step program that is on every night. But in any case, the self is under siege in this sense.

Now I don’t want to… here is going to be the problem of the lecture. It’s to try to give a sense for what the self was, sort of authentically, because that’s the really difficult nut to crack; is that I too am left with what one person who enjoys some of the paradoxes of chaos has called a “fractal self”. You know a fractal self, one that sort of reproduces itself… I am this over here, and this over here, I am a poker play here, and a lecturer here, and a TV star here – yay – and so on. But I mean, it’s not like this is some wisdom I can impart simply to you, but a joint project that I hope will lead to a conversation about it.

Okay, just a few more things here I need to get in, and they are very important. We are in a unique situation vis-a-vis meaning – the meaning of the self and our own human autonomy – it is a unique situation. For as far as I know – most of the history of this species – there have been culturally available reservoirs of meaning that were relatively stable and within which we could find a place for ourselves. Now this is not an argument to go back to any of those archaic structures. I am just trying to bring alive how they gave meaning.

I mean, a slave’s life had a meaning. It was a horrible and barbaric meaning from my perspective, but it was a meaning… and so this is not an argument for slavery. I think those are only made today by people like Pat Buchanan, I don’t have rational arguments to return to the institution of slavery. I am sure somebody on the far right will think of one for me, but I don’t have them.

But we have areas dominated by what are fairly called “world views”, where people find themselves within those views. They find a place that their life could have meaning within. In particular, and for our… for Western culture; the great religions have been such a place, within which people could find the, sort of, what you might call “Life’s final question”: “Why am I here?”, “What good do I do?”, “What’s the point in me being here?”, “Where do I go when I am through?”… big question. Job kind of had problems with that one; God didn’t really answer him, he just got pissed off. I mean, you know, if you have read the book of Job you know that God doesn’t answer the question, he just gets mad: “Who the hell are you Job, you tiny little mutant – what is this? – I mean I made you, I can make another one just like you, shut up” I mean this is… I am not saying God was wrong to answer that way; I am not in a position to talk about God that way.

As long as that could sustain people – faith in some kind of higher being – then there could still be a reservoir of meaning. And if you notice, that’s still the neo-conservative response; that we need a religious revival in this country. The trouble is – with that response – is that we have to pass through one, a set of complex intellectual manoeuvres, where we either know or suspect we know – and this will be, sort of, really to get around to the topic of the first lecture – whether we know or we suspect we know, that those belief systems have come under considerable suspicion, okay… considerable suspicion.

In fact, one of the legacies of the 19th Century, and this is the title of my first lecture which I am just now getting around to explaining, or trying to explain. The title of my first lecture is “The Masters of Suspicion”. There’s a wonderful book called “The Philosophy of Paul Ricoeur”; collects a whole series of articles by the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, and I am not interested in all the articles. He has one in here about the critique of religion, and in it he mentions the three great masters of suspicion of the 19th Century, and it’s not merely their intellectual work that began to make us feel estranged and alienated and separated from the holy world of previous times, the world in which we could find our meaning in God, or through his works. They reflect a seachange in the species view of itself. I would have included the name of Darwin… the first, you know, to give a natural explanation of how we got here.

In the case of Marx and Nietzsche and Freud; the reason they are mentioned my Ricoeur is they raise a criticism that I personally don’t see how any argument could get around. In a way it’s a counterpart to the believers’ faith. Just like the believer’s faith, even today, in the late 20th Century, if you want to hang onto it stubbornly enough can’t be shaken. Although that’s cold comfort given that any belief you want to hold onto stubbornly can’t be shaken, through the nature of human beings to be stubborn, obturate to reason and so on.

The suspicion they raise is much deeper, and I think Ricoeur puts them together well because when you are faced – and you will be, at least in some exciting intellectual context – with these critiques of religion, at first you will notice only the negative part; in other words, the destructive part of the criticism, and I’ll run through them quickly. I mean, they can be run through quickly because these names: Nietzsche, Marx and Freud; even Bill Bennett agrees they are all classics, okay? So we are not in here to convert anyone to any other religion or anything. These are classics. They are in fact markers in our culture of this seachange I am talking about. They put before us the problem of false consciousness; of the self being false to itself. That problem is one that religion was ill equipped to deal with. Ill equipped to deal with.

As long as we could believe with Descartes that if we knew something clearly and distinctly, we knew it, we were okay. But then when this suspicion crept in from the direction of Freud that we could know something, but it would really be a forbidden piece of our sexual history – prohibited and thus channelled in another direction – that was bubbling out of our little lips, then – and that consciously we would never admit it, I mean, by the way, not being a full blown Freudian, I do believe that sometimes a pencil is just a pencil. I think any one of these theories can be taken too far. But it’s clearly the case that the field of the unconscious undercuts religion in a very important way; gives a very profound explanation of it.

People go “Well, how could we not have a belief in God?” This seems to be most American’s attitude, even those who are not Catholics, Jewish, Christian, whatever; they just answer those damn surveys that you get in USA Today where 98% of them go “I believe in God”, which of course just irritates the hell out of me. I mean I grew up around Baptists that hated… they loved God, loved their fellow man, but they just hated folks. You know what I mean? They loved God, but they hated everybody they knew, I mean… you get a lot of that from the like the Jesse Helms crowd, I mean they just loved God, but they hate everybody else badly. Sort of irritating given then great religious traditions.

In any case, Freud raises the suspicion that we are very very small, we are very very insecure, we cry out to these larger beings for help and they give it to us, and we go “Oh, I see…”, but when we get older… and I think a very nice passage in literature is Ray Bradbury‘s “Dandelion Wine“, I hope some of you have read this book. It’s about a young man growing up in the Midwest, and he goes to the movies. It’s a cowboy and indian movie, he looks up on the screen – and he is about twelve, whatever – and he sees an Indian being shot. And he goes to cowboy and indian movies all the time, but today it occurs to him, Douglas, that he too one day will die. He goes “ooh”, it’s a bummer thing. So he gets out of the theatre and he begins to ponder that, you know “That’s really bad… I too, one day will die”.

Well, that kind of insecurity that we all have – I mean the only democratic institution, contrary to popular political theory in the world is death. Utterly democratic, it seems to me. I mean, if want something that is Democratic, there it is, its death. It’s utterly democratic. It seems to me that young Douglas is going to go to his mum and dad, and they’ll talk to him about it and explain how it fits and so on, and then will come that shattering night when you are about sixteen, and you find out mum and dad are afraid to die too… or maybe fourteen. And on a Freudian account, it’s not accidental that that’s the time you reach out for large and invisible fathers to protect you… and mothers. And you know what, that’s elegant suspicion. It is not an argument; it’s an elegant suspicion.

In fact when you look at the iconic significance of churches, you know the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost, the family values stuff, you know… I mean, I hate to sound cynical, but as Freud says, they whole thing is so patently infantile. So obviously infantile, that to anyone with the love of humanity it’s just sad to think that most people will never rise above this view of life. Well, when you have had a snotty German talk to you that way, you begin to suspect that he may be right, and this is one of the masters of suspicion.

Marx comes at it from a different direction. He has noticed that history is generally written by the sides that win. You may notice that terrorists are people who have not yet won, and after terrorists win they are freedom fighters, and after you have forgotten they are freedom fighters, then they are called chancellors or whatever. Marx has noticed this and he has also noticed the complicity of religion with this. And I don’t want to… see this is not about ragging on religion. This is about trying to explain why it could never be the safe harbour that it used to be. Because even for those of you with faith – I haven’t said I don’t have it – the faith is rounded in by what? Complexity, suspicion, doubt; and I am not talking now about doubt whether you, you know: “I doubt my faith…”, no I mean doubt that even if you consciously don’t doubt it, you’re still screwed up; you’re wrong. That’s the problem of false consciousness. That’s why it’s severe. It’s you could be absolutely clear you have no doubt, and it could be a pure abstract cultural mechanism, and not you… and not you.

In the case of Marx, what’s might be being masked is economic interest. I mean this insight has belonged to our culture too. I think many of you will be familiar with the Joe Hills song “You’ll get pie in the sky when you die”, and there is a certain style of American religion; I call it the Billy Graham style. I don’t dislike Billy, but it is notable that Billy Graham, you know, plays golf with the Pharaoh. I mean that’s not like Moses leading his people out of bondage, I mean, Moses didn’t play golf with the Pharaoh and pray over the Pharaoh’s troops. It’s just a confusing thing when you see that… it’s not like the story exactly. Hard to imagine Billy Graham being crucified, although I have suggested it on occasion, ah… people don’t seem to listen. I try… I try… I am not saying there aren’t any religious figures that are significant in the 20th Century; there are magnificent ones like Ghandi, Martin Luther King, they appear as rare exceptions… rare exceptions. I mean, there people who still try to lead their people out of bondage; not everybody plays golf with the Pharaoh, but the suspicion hangs on the entire religious enterprise that it serves vested interests: economic interests.

To be blunt with Marx, and I enjoy a blunt account of everything, that they are involved with that shit called money. The fundamental criticism Marx has of capitalism is correct. Communism is stupid, but the fundamental criticism is correct, and that’s that our being is shaped by that… merde… that “yuck” called money; still is. Does that reduce complexity? Not anymore it doesn’t! Money flows around the world in tiny little circuits, we carry it in our pockets in little computer cards, we beg for it, we have one little note on our credit history and we can’t get a loan for a car… just… even money isn’t simple anymore. I mean some people pray for the day when there used to be highwaymen, you could at least stop the coach and go “Give me your money” and get money. Now you can’t even go to the bank and get it, and I thought they had money at banks, but no… they don’t. You go in “I’d like some money” “Nope, we don’t have it, sorry”. You don’t know where to go then; that’s confusing. This is complexity. [cough]

Okay, the third critique of religion comes from Nietzsche. It’s about the reversal that comes about when the religious, as it were, trick themselves about what they are really doing. And I think that there is great examples of this, and I am going to go for the easy examples since I am running out of time, okay? Is that fair enough, I am running out of time for the first lecture; I’ll go for the easy examples. And these examples of course are Christian televangelism, although… although subtler forms of this are always possible. It’s like television, you get the crude quick version on TV, but because everybody – practically – that we are around was raised by it, then they give you the slightly more complicated human version of what brought them up: their televisions. Pretty scary. That’s why the self is under siege; all of these are reasons why it is. [cough]

Nietzsche has noticed that something has happened like the following. I’ll try to sum it up with something I heard one night Jerry Falwell say. By the way, this is all philosophical. Don’t get confused, when we do philosophy my way, we just talk about what is going on and try to find our way about. Because my negative remarks were if you think that John Rawls from Harvard can come up here and help you with this problem then its useless. I mean, I can’t either, but we are going to at least talk about my inability to do so. There is a difference. I call that the Socratic difference. I am willing to talk about my inability to figure out who I am and my guess that most of you have the same problem. Well anyway, let me go back to my Falwell story because it’s too funny to leave out. Anyway, I think it’s funny.

Falwell has a line where he goes, you know: “I love the homosexual, but I hate his homosexuality”. For Nietzsche that’s a profound Christian remark. “Oh we Christians, we love our enemy… we love our enemies. If they hit us, we don’t even hit them back, but some day our kingdom will come” You have seen the bumper stickers “Someday our kingdom too will come”, of course they say that because people are supposed to be so very humble in all they say. It’s an irony not appreciated by everyone. The greatest passage here I have used it in a tape before, so if you have the other tape, just replay it now… no… [laughs]

Nietzsche has the wonderful quote where he goes “Dante, I think committed a crude blunder” – which is already a fairly arrogant remark, but he is a German, so what the hell – “Dante, I think committed a crude blunder when above the gateway to the Christian hell he placed the words ‘I too was created by eternal love’”. I mean, that is in Dante. Above the gateway to hell was “I too was created by eternal love”. Nietzsche says it would be truer to place above the gateway to the Christian paradise “I too was created by eternal hate, provided that one could write a truth above the gateway to a lie”. See, people that write that pungently raise suspicions in our minds, you know, they raise these suspicions, and it’s not just them.

If you read Saint Thomas carefully – and I am not talking now about one of these renegade 19th Century figures that set the stage for this sort of problem of meaning we are faced with in the late 20th, but Saint Thomas Aquinas himself says that among the chief pleasures in heaven will be that God will be kind enough to let us see the torments of the damned. Meanwhile we live in faith, in hope, and in compassion.

After these three are through with our intellectual culture: Marx, Nietzsche and Freud, no-one can believe. No-one. It’s like childhood’s end for our culture. You follow me. It’s childhood’s end. You know how you can believe something when you are a child… and it’s not like you can’t come to believe it again when you are sixty… you may be cynical about it again until you are sixty… but these critiques mark childhood’s end in regard to finding meaning in that religious framework. I mean, Paul Ricouer has a beautiful phrase for it. He says, ah, the positive significance of these, ah, criticisms I have mentioned is what they have in common… and that’s their iconoclasm. The fight against the gods of men. That’s very interesting. In other words, their iconoclasm is their fight against the gods we have created so far. And that is what they have in common.

He goes on to say: this atheism that we have just discussed… this attack on the god, or the gods of men… is not of the kind that some contemporary philosopher is going to get up and dispute. Because this has to do with the very things that form the consciousness of the person who would be willing to dispute it. In other words, you’ll never know, after Marx and Nietzsche and Freud whether your argument is an argument or a symptom. You follow me? You won’t know whether you have got a good argument or a bad symptom. You just… there’s no way… that’s the problem of finding your, you know, real self here.

And ah, Ricouer himself is a Christian, and so he says the following: “A Marxist critique of ideology, a Nietzschean critique of ressentiment and a Freudian critique of infantile distress, are hereafter the views through which any kind of mediation of faith must pass”. Now, does that mean that every ordinary religious person has to know these writers and stuff? No… these suspicions have become widespread in our culture. We don’t need anymore, in a way, to be instructed in them, because they permeate our culture. This is what conservatives complain about, in a way, they go: “Well, you know, every time you see a Christian on TV; he is either out for money, or he really hates people, or it’s some sexual thing.” Where does that come from? See, the cultural critique of these people has insinuated itself everywhere.

So, the first thing you think when someone comes on a little too strong with religion, is you start running through the “Masters of Suspicion”, going: “What does he want? My billfold? What kind of… is he on some bizarre sexual trip? Is this another Jimmy Swaggart thing? What kind of power trip is it for him?” You know… I mean, we have got guys some of these guys in Dallas now who just get on TV and say “Give me money because God says for you to give me money. You give me money, and you’ll get some money back. Not from me, but from God.” He’ll keep God’s money. And you’ll get money from God. And that’s a nice… deal… between him and… God. It’s a wonderful… advantage.

Okay, now, the reason I have spent so much time on these “Masters of Suspicion” – the title of the first lecture – “The Masters of Suspicion”… these were critiques that were developed in 19th and end of the 20th century. They have become a common possession of our culture, and they have cut off one of the reservoirs within we might find a coherent meaning for our life. One of the reservoirs being religious faith. Not entirely. It’s not like we can’t go back and have it. It’s that we must have under the mark of complexity… follow me? Under the mark of insecurity. Under the mark of confusion about it. It’s not that you can’t… it’s just under those… marks.

And then I think that I’ll close this first lecture with a brief little story from the movie “The Big Chill“. Now, I hate the movie “The Big Chill”, let me make that clear, and I hope I can’t be sued for hating a movie, I hate “The Big Chill”, because it’s about members of my generation, all of whom have become swine. The only person in the movie I like is dead when the movie starts, and they are having his funeral, and the old preacher says something quite profound. He asks the crowd of young yuppies, he goes “Isn’t our common life together and just being a good man enough to sustain us anymore? And the answer to that is “No, it’s not”. It’s why people hate Bill Clinton. The symbolic reason they hate him is there was this background of Kennedy-esque meaning that he was supposed to deliver, and it turned out that he was just another slightly overweight Southern guy and out lives don’t mean any more than they did a year ago. And we are pissed; we are mad at him… we are going “Damnit Bill, we wanted an adventure, we wanted meaning, wanted hope, it’s not just tax and spend”; of course if you ask somebody “I want your money, give it to me” they don’t like you, but I mean, they can’t figure that out either, that’s part of the problem of politics. In any case, the question in “The Big Chill” is what I want to conclude with, and that’s the rhetorical question the preacher asks. Unfortunately with the self under siege in the late 20th Century the answer to that is: no, our common life among our fellow human beings and leading the life of just a good man or woman is not enough to sustain us anymore. It’s a shame. [applause].

Thanks to Rick Roderick.org

Good effort on this one, Mike. It must have been painful inserting all the hyperlinks.

And yes, these these are certainly worth a watch (unless East Enders is more your cup of tea, in which case there’s no hope).

I must admit i did not do that someone else provided that text

Good post regardless.

Good post regardless.

Good post regardless.