This is the sixth of a great series of lectures about modern life and the post modern condition by the great Rick Roderick the Bill Hicks of Philosophy. What is great about this series is that Rick delivers it such a great way that is very easy to understand, he makes difficult concepts clear and illustrates them in a interesting and engaging way. When I first found these lectures, I had to watch all of them one after another great and I urge you to do the same. Below the film is the transcript of the talk and a summary of the main points, but please watch the lectures first as they deliver a lot. Enjoy and raise a glass to Rick Roderick who unfortunately is no longer with us.

This is the sixth of a great series of lectures about modern life and the post modern condition by the great Rick Roderick the Bill Hicks of Philosophy. What is great about this series is that Rick delivers it such a great way that is very easy to understand, he makes difficult concepts clear and illustrates them in a interesting and engaging way. When I first found these lectures, I had to watch all of them one after another great and I urge you to do the same. Below the film is the transcript of the talk and a summary of the main points, but please watch the lectures first as they deliver a lot. Enjoy and raise a glass to Rick Roderick who unfortunately is no longer with us.

Summary of the lecture:

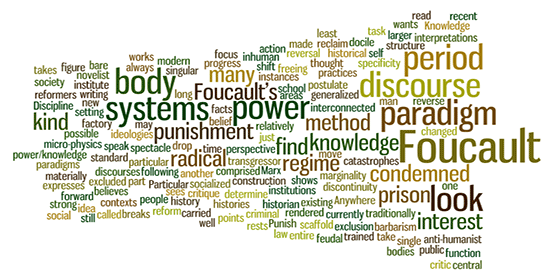

- Foucault is a strong anti-humanist who believes that “man” is a relatively recent construction of a particular historical paradigm. Such paradigms structure discourse and action, as well as institutions and belief systems. They are, at the same time, systems of knowledge that are always interconnected with systems of power. Anywhere you find knowledge, there too you find a regime of power.

- Knowledge is comprised of discourses that function through rules of exclusion. These determine who may speak, about what, for how long, and in what setting or contexts.

- Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish” shows how the paradigm of punishment and the law shift from one period to another. In the feudal period, we have “the body of the condemned” as a singular figure and “the spectacle of the scaffold” which expresses the criminal as a transgressor and our interest in him.

- In the modern period, we move to a paradigm of generalized punishment; from the body of the condemned to the entire social body (public works, school and prison reform). The reformers in many areas institute a micro-physics of power over the “docile bodies: of the “trained” and “socialized”.

- Foucault’s method of writing his “histories” rests on the postulate that there are no bare “facts”, just interpretations and these are themselves only made possible by the currently existing regime of power/knowledge. Particular to his method are the following:

- reversal, that the perspective of the standard history and reverse it

- marginality, takes the focus off what has traditionally been thought to be central and look at the excluded

- discontinuity, drop the idea of necessary progress and look for breaks and catastrophes

- materially, look at practices more than at ideologies and

- specificity, take single instances to illuminate larger points.

- Foucault wants to reclaim a kind of radical critique in the interest of people rendered inhuman by what he sees as the very discourse of the “human”.

- Foucault can be read as a novelist, a historian, a radical critic of society, and many other things. Most importantly, he has changed our discourse from Marx and the “factory” to Foucault and the “prison”. He has carried forward at least a part of the task of freeing a new kind of self from the barbarism of what is still called the past.

Transcript

In our last lecture we discussed Habermas and I think that we left out at least one thing I need to begin with before I proceed with Foucault and that’s Habermas’ view of the self as a thoroughly social being, that is; the interaction of the natural world, the social world and the inner worldof human, as it were, suffering, sympathy; a subject entwined in desire. Those are the three dimensions to subjectivity that Habermas discusses and he sees each one as challenged in the late 20th Century; so I wanted to add that to maintain our subject under siege theme.

Habermas’ account that I have just finished is, as it were, one of the more optimistic accounts – if you will use a word that simple it’s one of the more optimistic accounts – but it still does not relieve the subject of the incredible pressure to construct meaning and conditions for communication under conditions that are very unfavourable for that to occur. I mean, that’s still part of his account.

We will now move on to a thinker who at least in a couple of respects is like Habermas and that is a magnificent… it’s hard to characterise him as a philosopher and no-one knows exactly where to put his books; we don’t know whether he is a historian, a philosopher, a sociologist, in fact that’s almost the mark of late 20th Century thinkers. It certainly is the case with Habermas that we don’t know where to stack his books and similarly with Foucault. They move across disciplines and I think that’s very important. So that is one thing they share in common; it’s difficult to know the disciplines they are in.

Another thing they share in common is an interest in emancipation. In other words we are again talking about in this case – not as in the case of Habermas, a “left liberal style thinker”, to use an American phrase here – we are talking about a very radical thinker whose politics like the politics of Noam Chomsky – who the last time I checked wasn’t American – like Noam Chomsky’s politics, this is a person who is what I would call a “principled anarchist”. Now he has a difference though; he does not, in a way, have his politics intervene in his writing nearly as much.

In his writings, what he tries to do is to develop a fundamental critique of what I might call our dominant ideologies which is what I would call sort of centrist. A little liberal this, a little conservative that, but he tries to develop a powerful critique of what you might call the dominant paradigm within which we do our politics, within which we run our educational institutions, within which we operate our prison systems, within which we operate various psychiatric disciplines and so on, and he does this in a different way.

Unlike Habermas whose account is very abstract – if you noticed – Foucault enters his topics through the avenue of what might be called histories, but they cannot be understood as history in the traditional use of that word and so I will start by giving a brief account of some of the jarring things about Foucault. One is that Foucault is infamously known for holding the view that there are no facts apart from interpretations. So for Foucault there are no bare facts in history. In other words there aren’t just little facts you run across separate from the interpretations within which the facts were embedded.

So this makes history look like a kind of battleground. In other words “you have got my story and I have got mine”. As a matter of actual historical practice, when you read historians, I don’t think this is a bad description of the way they actually work. I don’t know why certain neo-conservatives like William Bennett find this to be relativism, when I see it as a just good description of the way historians actually practise their craft, and its not a simple minded thing like “everyone has an axe to grind”, it’s not like you don’t get surprised even based on your own interpretation and its also not the case that as you work through your interpretation you do not change it radically and change your mind and your prejudices, in fact, when you do that, that’s when you are doing your best work usually. So I don’t see this as outrageous as many other people do.

Now the word “history” itself is avoided by Foucault, because he thinks that the word “history” within Western Civilisation is necessarily a kind of continuous narrative about progress. So Foucault prefers to the term “history” terms like “archaeologies” and “genealogies”. You may notice that this is some of the influence of Nietzsche on Foucault. Nietzsche wrote a wonderful history of moral life as it had arisen in the West, but he didn’t call it a history, he called it a genealogy.

So what is the difference between genealogies and histories and at least these following conditions are ones I have been able to pick out in Foucault’s work. One of the methods that’s different in a genealogy and a history is what might be called a reversal of perspective. Now this is one he takes from some of the better historical work in the tradition of Marxism, and that’s where, and I mean Marx is famous for this, but so are some people you should know about like E. P. Thompson who wrote The Making of the English Working Class and C. L. R. James, a wonderful Caribbean intellectual who wrote The Black Jacobins.

This is reversal of perspective where you don’t write history from the standpoint of Henry Kissinger but the standpoint of the masses of humans that do the masses of things that they do in order to produce large and significant movements that change formations – social formations – and this is really to take sort of a reversal of perspective. You take, in a way, what was left out of the official histories and use that as your clue to write a history of suspicion that something has been left out.

A history like that of the American Revolution would be fascinating and I know at least one person – Larry Goodwyn at Duke – who is working on such a project. Well anyway, reversal seems to be a method of genealogy. Another is one connected to it and that’s marginality. You don’t just pay attention to what the leaders said – or the men said, or whoever the dominant group is – you look for the marginal discourses that do two things. They both make clear that there was a marginal discourse and they also show more clearly what the assumptions of the dominant history or discourse was. So marginality is another feature of what might be called a genealogy or archaeological method.

The third one seems to me just a very practical principle, its the principle of discontinuity, and that means write your history without the assumption that history is continuous, without the assumption it will end up being a rational story, without the assumption it has a beginning, a middle and an end, but rather accept history in what is called its “materiality”, in other words along with all of its contingencies, its moments of luck, the strange and bizarre things that happened…

I mean, even Marx does this when he writes the history of the rise of capitalism, it just turns out to be fortuitous that gold is found in the new world, which then can be sent back to Europe to build merchant capital. Well if over here they had found cow chips only or buffalo chips, then that contingency would have effected history, and that seems to me just to be not something that could have been predicted by a rational narrative. They happened to find gold, you know.

So don’t assume that there will be, as it were, a telos…

…and this is deeply embedded – telos means goal, or purpose – this is deeply embedded in the way that Westerners think because… I think, in a way, because of narratives like The Odyssey, where there is a beginning, a middle and an end and narratives in particular like the biblical narrative where you have an absolute original beginning, you have a redemptive middle and then, you know, a final and glorious end, and this mode of thinking has effected historians for years. Foucault does his best to, as it were, try to bracket or stop those assumptions from interfering with the way he wants to write history, or I should say, the way he wants to construct his genealogies.

Okay, now, here is the claim I think that is the most outrageous of Foucault’s and about which a lot of the debate that you hear today about “deconstruction” – even though Foucault is not a “deconstruction” person – a lot of the debate you hear today about the universities hinges on this important claim by Foucault and I will start with it and I will defend it and then I will give you an example of a powerful work in which he makes use of this claim. The claim is as follows: Knowledge is controlled in every society through mechanisms of power. Anywhere you find knowledge; there also you will find power. They are linked. They are conditions for the possibility of one another. “Knowledge is a regime of power” is how he sometimes says it.

Today, in using the distinction I have used in these lectures, I might want to replace the world “knowledge” with “information”, and it wouldn’t hurt Foucault’s argument if I did given that I think that’s what the university systems and other systems produce; that’s a better term now for it. But in any case, the idea here is that it cuts deeply against a lot of our humanistic sentiments. We would like to believe based on the long Platonic tradition that knowledge is what can be accepted by all rational beings, and the standard model for that in philosophy is mathematics. You know, one plus one is two and you don’t vote on it and it doesn’t matter what you think, and you know that’s probably right about one plus one is two. But its a far different matter about whether its right about the structure within which we learn systems like mathematics, and that’s what Foucault was concerned with are whole genealogical slices of time within which we learn certain practices and how to obey them.

Now when I have my students argue with me about this thesis that: where you find knowledge or information there also you will find power, if they keep arguing with me I threaten to given them a “C” and then they agree with me [crowd laughter]. And that is what I call a demonstration by direction, or a West Texas phrase for it would be “hitting a mule upside the head to get his attention”; that will get a student’s attention, when they realise that your power is connected to your knowledge and vice versa. By the way if they happened to be the son or daughter of a three or four million dollar donor to Duke then their power is connected to how their knowledge may have to be treated by someone, although I generally ignored that kind of thing, in fact I have always ignored it.

Alright now that’s the thesis that is considered – as hard as it may be to believe, because I think I presented it in a commonsensical way – this is the thesis that seems to have outraged a whole group of people at universities as though this doesn’t speak to the experience of – and of course it does, this is why they associate it with political correctness, because this always spoke to the experience of those who have just entered such systems; women when they first came to the university, African Americans, Chicanos and so on have always experienced the knowledge that they were to receive as a form of power and this certainly was true of the working class kids that entered the university system in the sixties, you know as I said, thanks to a lot of student loans that Lyndon Johnson was responsible for, which I will give him credit for since his friend John Connally recently ah… kicked off.

In any case, this has seemed to me to be obvious, but it has caused a furor, you know, a real ruckus. It’s as though someone has sort of given away the secret. I mean, I don’t think there are that many people in serious, quiet conversation that don’t recognise this relationship, but it’s not one that we like to talk about publicly and that’s…

Even a graduate student we have in physics that we take a particular dislike to and who comes up with equations and views about Newtonian dynamics that are say, at odds with various more contemporary views relating to chaos theory, we can call him old fashioned and kick him out, or if the reverse is the case, we could say he’s a kook and his work is too flighty and too bizarre and kick him out, I mean clearly there is a relation, it seems to me, between knowledge and power. It is a mechanism that has operated, I think, in every society, the issue is whether there is any way – and this is going to be the happy issue; will be whether there is a way – to uncouple knowledge and power. I will leave that aside for a moment as I move through this thesis.

Knowledge is comprised not only of institutions – and I will be naming them later – or institutional rules and so on, but of discourse, and this is where we get back to Habermas and relating to communication. Knowledge is – or knowledge and information is – comprised of discourses, communications that function through rules of exclusion, not inclusion; through rules of exclusion.

In other words, institutional communications function through rules that determine who may speak, about what they may speak, for how long they may speak, in what setting they may speak, and so on, and again, this is not an invidious thing, all societies had these. You may notice if you watched the congress that there are rules for how long people may speak; they are rules for who may speak. If you are a freshman member, its not advisable to hog a lot of the clock, this is not an advisable thing to do.

And I don’t want to make it appear invidious in every case but also we need to see these rules of exclusion as leaving out of what some sort of liberal theorists like Richard Rorty call – and I mean I can’t believe that they ever called it this – Richard Rorty once described philosophy as “the conversation of mankind”; borrowing a phrase from Michael Oakeshott.

Well that’s very nice, except certain people didn’t get to talk in the history of Western Civilisation. They were excluded from the conversation. The deviant were excluded – and I am naming some now that have been studied by Foucault – deviants, criminals, the mad, and of course the more normal exclusions. Up until very recently women, the young, the old, the infirm, and so on; excluded in a certain way from this conversation, and I am not afraid to say along with Marx that we really don’t notice many working class or lower class people in the early great literature of the West.

In all the works of Homer, only one common foot soldier appears and he has one line, basically he says to Nestor, you know, the wise old General the plan basically sucks and he walks out of the book and that’s it [crowd laughter] And of course it does, and so it’s kind of a little joke, I think Homer was aware that certain people weren’t getting to talk.

So when we talk about Athenian democracy we need to remember that just like early American democracy it excluded a lot of people. In fact, according to Foucault, the exclusions were a condition for the possibility of that being a form of knowledge and discourse. In other words, it wasn’t, as it were, by accident that these groups were picked out, they were picked out because their marginal discourses would allow the main discourse to be even more in place, in control and so on and this seems to me at least to cut very strongly against Habermas’ communication theory because if it is the case that wherever we find information, communication and so on, we also will find power that controls the ways in which it flows; who may talk, when and how long, if there is no way to uncouple that then Habermas’ argument will fail. Foucault does not say it will fail. In fact, Foucault himself, because he holds a radical anarchist position is caught in what I would call “the critics’ paradox”.

The more powerfully the critic paints the ills of the society and the fragility of the self and the struggle it undergoes to be a human; the more powerful our account is, the more hopeless the people feel who could do anything about it. On the other hand, if we don’t paint the account in such a powerful way then people tend to underestimate what they are up against, so you have got a critic’s dilemma. Foucault clearly has picked the path where he doesn’t care if you feel powerless or not; that’s your problem, you have got to do something about it, so he draws out all the mechanisms of control to the maximum so that you understand them.

Okay, he wrote a series of books; I am going to use one as an example of his thesis that knowledge and power are intertwined and the effects it has and I am going to pick one of his most famous, but let me quickly give you a set of the books that he worked on. He wrote a book called “Madness and Civilisation” in which he pointed out the long history of how the discourse of reason had excluded from it the mad. Now this history changes, as you know.

In the medieval period, the mad are considered the way they are… How did the mad appear in Shakespeare’s’ plays? The fools, the mad. Well they appear as the people who bring the most important wisdom into the plays. They have… the mad in Greek society were considered as touched by the gods; their words were looked at almost as the words of oracles.

But with the increasing, as it were, with the increasing rationalisation – a word I have used a lot, and a word I used yesterday – rationalisation of the world the mad began to be shut away in asylums. At first this was a brutal process and later it became “humanised”. This is a word that Foucault does not like. In fact he doesn’t like “humanism” or the talk about “humans”. He is afraid every time he hears it that it is not a word of inclusion, but of exclusion, based on the history of the use of that word. I think African-Americans can particularly relate to that since only within the lifetime of a couple of generations have they become more that three fifths human; they can understand what it means for it to be a term of exclusion.

In any case, the great reformers of madness were the ones who wanted to, as it were, cure them created what Foucault calls a whole new disciplinary matrix around madness. What that means is that the curing of them did not liberate them, it did not give them the value they had at one time, no it set up a whole series of processes within which they could be observed, drugged, analysed, re-analysed, and of course I have joked about this process. I don’t want to use the strong word “madness” here but when we look at the expansion of this therapeutic zone on into the late 20th Century, we now find out that very few of us don’t belong in it.

I mean, if you are not on a twelve step program today, you are out of fashion. I mean who would have guessed that the discourse of madness would eventually cover the whole social field until perhaps the last growth industry we have other than making movies about sex and violence is psychiatry and running twelve step programs; this is a growth industry. This is one industry where you could, you know, retrain yourself in midlife – since you don’t need a degree to do this actually – and set up a twelve step program.

So for Foucault this is not some great new humanistic advance in medicine that has liberalised the treatment of madness, it is a new form of control that’s based on a new language about the mad. For example we no longer call them morons and idiots; we call them the differently abled and so on. But for Foucault this new discourse is even more totalitarian because behind it hides the same mechanisms of power… not the same… but behind it hides mechanisms of power which keep these people in their sway.

I think that one of the greatest examples of this – for me – is the discourse concerning body weight in women; bulimia, anorexia and so on. It’s as though a male dominant society was able in the Middle Ages to, you know, put a chastity belt on a woman, to put, you know, to keep food away from her and starve her if she misbehaved. But today we accomplish the same feat through images that are constantly bombarded into the conscious and into the unconscious of women, and they perform the wonderfully humanistic task of starving themselves to death while male therapists teach them how to get onto twelve step programs to eat. See, for Foucault, this is why its not humanism.

This kind of malady is a cultural malady that strikes at the very heart of life. Once something like eating is death then you have struck at the very heart of life. The enemy of the older radical theories may have been the ruling class, but today the stakes of whether we will reform ourselves into a new kind of human being, a new kind of society, whether we will find selves worth being; the stakes of it are simply life itself and that makes it quite dramatic actually.

So that’s an example of Foucault’s account – not from him; I made that one up – Foucault died of aids, he’s not still alive unfortunately, so he didn’t get a chance to write that one on fat and skinny, but he wrote many others. On the normal and the deviant he was in the process of writing a long book on the history of sexuality and then ironically before he could complete it he died of aids. So the book I have decided to use is his famous work and I’ll show it to you and suggest you all read it: “Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison” and I intend to go through the argument in some detail because it would be very much against the spirit of Foucault to give you all the abstractions about his position but not give you the really important points where he works out in detail how these interlocking systems of knowledge and power actually function in his genealogies. That’s the real meat of the story for him, so I am going to go through this in some detail, at least the detail that the constraints of time allow me.

Discipline and Punish begins with a very short chapter called “The Body of the Condemned”, and this is in the period, I think 17th, 18th Century period… at this period in history basically takes place in France, but similar practices were also taking place in England and in other of the countries that were on their way from merchant capital to an advancing capitalism, but still this is pre-revolutionary France so you still have a king and France is run by the red and the black, you know, the red of the church and the black of the army, that’s a famous novel by Stendhal for you people who still read novels, The Red and the Black; it’s worth reading.

But in any case, The Body of the Condemned begins with a famous and hideous passage which if I read then this tape will probably be censored, and its about the way they killed people who committed horrible crimes. Now today when people commit horrible crimes they are on A Current Affair for three or four nights, right? Two or three books are written about them, they make a movie about them like “Silence of the Lambs“, and then they are locked away somewhere. That’s where we are moving… that’s where we move to, but let’s start from where… how we got there.

The prisoner that he begins by discussing is drawn and quartered and torn apart by horses; I’ll make this brief. Lava is sort of – or sulphur – is poured into his wounds and set on fire. Now I don’t need to go into detail; you understand these medieval tortures; they are well known. The condemned man must, as it were, the priest comes up and the condemned man must make his honourable announcement before God that he understands the justice of the punishment, and of course after the punishment has begun this is not a hard thing to get him to do, and so the book begins with him kissing the cross and making his “honourable amends”; would be an English way to say it, and then they continue to torture him and literally on his body is written “the power of the king and the church”. In other words, it is literally written on his body.

By the way, if you want for me to suggest another literary way to look backward at that form of punishment, remember The Penal Colony by Franz Kafka where the machine writes literally on the bodies of the victims. Of course Kafka has lived to see modernity, so the machine ends up eating its own judge, writing on the judge “be just” which I find among Kafka’s many hilarious stories. I mean, I find them funny, I am sorry, I am that sick, but I find that another funny one.

In any case, it starts with the body of the condemned, and the next chapter is about the spectacle of the scaffold and all of the ritual that goes along with these kind of ceremonies. When they are going to do this, you can imagine the streets of Paris, they are all abuzz, the spectacle, the scaffold. There are vendors, there are people that write little pamphlets about the executed. I mean, we have an American analogy to that, that’s like, you know, the little Billy the Kid pamphlets that were printed up in the early west about our great criminals and so on.

Foucault asks this very interesting question. What was it that fuelled the interest in the criminal? Why was the criminal the star of this production, this scaffold, the spectacle of the scaffold? He’s the star! Well, the crowds became unruly because in many cases the courage of the criminal would become the legend of the spectacle. The courage, the tenacity and the bravery would become the story. Well, reformers decided that this was not a healthy mode of punishment. Foucault cynically decides that perhaps it was not considered healthy because the wrong people were the stars of the show, not because it was too barbaric, and I think that’s not only a cynical guess but he gives some evidence that that’s the case.

In any event, we know that this early history of punishment from the middle ages at least, or the early, sort of, pre-capitalist days, this interest in criminals has continued on into the present. I mean they still haven’t found a way to discipline and punish that have totally drained us of our interest in criminals, as you know from watching any television. Even if you hate it, you have got to know this.

I mean, I think that Time-Life now is going to put out a series of books – I am not denouncing them for it – on criminals, but this is nothing new, right? These are things that excite us as the normal because they break up the regime of normalcy and show it in a way for what it is. I mean just as the king wrote his punishment on the body of condemned; the mute body of the prisoner – even if he said nothing – spoke volumes about the institutional rules that would put that practice in place… that would put that practice in place.

Well anyway, that practice was abandoned, it has been a while since we have drawn and quartered anyone although when you listen to some of the latest rhetoric about law and order I don’t know how much longer it will be before we will be drawing and quartering people again, but anyway, that practice for at least the present has been abandoned and it’s replaced, according to Foucault, by what he calls “generalised punishment”. It’s very interesting. The French word might lead us to believe that this is a sort of double word, it’s not only punishment, it’s also a kind of – the word discipline would be – a kind of surveillance.

So what happens is the change… what Foucault is writing in this book is a history of criminology, in a certain way. The change here is that we move from the body of the condemned as a singular individual – “Billy the Kid”, you know, to use the American example – to a generalised social body. Criminals now appear not with names but as public enemy number one; I mean, anybody could be that, you know. In other words it’s a general abstract role, it’s across the whole of what could be called “the social body” and in fact we now see punishment… and of course… I want to make this just as cynical as it is; it’s the great reformers that are responsible for this. This is the work of the liberals, I mean the conservatives wanted to continue to draw and quarter people, but no, let’s reform.

The great utilitarians like Bentham, which I will mention – whom I shall mention again later – were among the reformers that led the way in some of these areas. When punishment becomes generalised across the social body; across the whole of society, what happens is that punishment becomes something like public works. You know, this is… you do a small crime and you go out and you do works for the public. But like sweeping up can’t be as heroic as having the king’s name written on your body, in fact its rather degrading, it’s not supposed to be something about which one can write a damn novel.

Prisons become more like schools and less like these festivals of atonement. They have become places where people are to be re-normalised, injected back into the social body if possible. What the reformers have done according to Foucault however is not to abolish power in favour of more humanistic treatment, what they have done is to institute a micro-physics of power that has control over what Foucault calls “docile bodies”.

Power has lost its awesome grandeur; its splendour. The power now in institutions like prisons is a micro-power, its power of observation, of being able to control movements, of being able to force prisoners into “get well” programs and lie to their parole boards after having lied to therapists, after having lied to all the various people they have to lie to in order to get out.

And for people who think that prisoners are being let out right and left, watch a little Court TV and see how many people actually win parole. Now in some states where they have stopped building prisons because they are tired of “tax and spend”, some prisoners do get out, but by and large it’s hard to get through a parole board.

What this parole board represents to Foucault is a kind of training, a kind of disciplining of the body so that it no longer has to be written on in these grand spectacular letters but in which the prisoner himself accepts being a docile member of the social body, who goes to prison and simply accepts as a Fait Accompli the very rules of this humanistic institution.

Let me give you an example, and again, this is not a prison, but this is a great example, and I hope you have seen the movie – I like using examples from movies – and if not, there is a great movie by the same name; before the movie, and that’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, written by Ken Kesey, the movie stars Jack Nicholson. There is a great reformer in the movie, she is a wonderful woman and she is there to help the patients. It’s Nurse Ratched.

Nurse Ratched just demands docile bodies. Randle Patrick McMurphy‘s doom is that he cannot become a docile body; he’s an anarchist, he’s doomed, he’s excluded. He’s excluded, but not really, actually he’s helped. I mean, he’s lobotomised, you know, the lobotomy calms him down; it makes him normal, docile, like most of us.

Of course if you have seen the film or read the book you may begin to understand what Foucault was driving at. You know, if McMurphy had been born 200 years ago he would have lived the grand destiny that maybe Billy the Kid did, Billy the Kid being probably in real life a psychotic teenager. The sad story about him is I am sure that the eastern writer’s way overdid it, but then that’s part of crime isn’t it? I mean, this fascination with it has not ceased simply because power has reconfigured it.

Okay that’s one example, but I don’t want to leave it with that example at all because we get in the great reformers some clues as to what they are up that are magnificent and some of them related to architecture and that’s very important if you are to understand the point Foucault is driving at, which is not simply about prisons, although they are his – prisons and criminology – are the focus of his study. He is trying to point out that we have a society that is an entire carceral body; a social prison within each one of us have certain safe walks and certain excluded walks, and all of them are surveilled and our behaviour is surveilled.

You know this, you have walked in malls and the dummies now – you know, the clothing dummies – frequently have these little cameras for eyes so that they watch you while you shop. I mean, this is… I don’t want them watching me when I… I am so overweight, when I am trying on a new pair of pants, I don’t want to be… have some anonymous person in a booth watching me try on my new pants… I just… but surveillance isn’t like that, and I have not yet achieved the status of docile body myself, but anyway.

Let me bring in Bentham again. Jeremy was not only one of the great utilitarians about whom you will hear in a course on the great minds, he was also and architect and he had some drawings of a building called the Panopticon, which as he says, could function as a prison, but also could be made to function as a university or a school or a hospital, because it has this odd feature. It’s a sort of circular building within which the administrators can see down through every cell, but all the people in the various cells of the institution can see is at most the person across from them and usually not that.

It is not the building itself that I am so interested in, just like Foucault says I am not so interested in the building itself but the principle. The panoptic principle; what he calls panopticism. It is a hierarchical principle that allows the gaze to be directed unilaterally. I like to call it the CIA feeling, even though I think that the CIA is now largely obsolete; it’s the CIA feeling, it’s that they are looking at me, but how do I know when I am looking at them. That’s panopticism and this is not just a feature of prisons; this is what Foucault points out. In fact it’s very… its hilarious.

Many of the same architects that built our prisons in North Carolina and elsewhere also build or what? Our schools! Our hospitals! All of the places in which we want to keep, contain, and control docile bodies, docile social bodies. For this reason Foucault extends as a generalised critique of our society that it is in fact a prison. It is a carceral gulag, I mean, that’s strong talk… that’s strong talk. But if you think about my example of bulimia and anorexia, there is no prison that could lock a woman into more terror than that experience.

There is no prison and no medieval torture that brings to mind this, sort of, slow death of the soul by degrees that a docile body suffers as it walks through all these routine and laid out paths of life being constantly observed and the current fascination with criminals, I view in the context of Foucault’s work – it’s not that current, I mean in the 30′s they loved gangster movies too, but this fascination with criminals is the compensation the media culture pays to us because of our secret attraction to crime, not because of our fear of it. The attraction of crime is the attraction of someone who says “Hell no! I won’t play that way anymore!” and I admit that one level we are afraid of criminals, we don’t want to be hurt, people don’t want to be hurt, I am not arguing that, that’s not… the argument is at a whole other level of institutional rules and expectations.

In our society, in the United States, these rules include many rules of ethnicity that they wouldn’t include in other societies, although there they have their own ethnic problems. But is it not accidental that at Duke and at other universities like it, African-American makes on campus get arrested with some frequency, at least detained, and it can sometimes be embarrassing when they turn out to be one of our new power forwards. So I mean, they go “Oooh, he’s a power forward, let him on his way” No, it is that there are walkways through an institution like Duke where certain kinds of people are expected to move docilely and others are not. These are the exclusions that I am talking about.

You find this in malls; it used to be that a mall was just a damn place to go to shop, now not everybody can get in the mall. You know, if you are wearing a big baggy sweater and you have got an X hat, you may not be able to get into the mall. Not that I want in one, I am a person who suffers from mall fever. Mall fever may be the last symptom preceding the death of what Foucault would call “the docile body”. Well anyway, thankyou very much, that’s as far as we could get with Foucault, thankyou. [applause]

Thanks to Rick Roderick.org