This is the seventh of a great series of lectures about modern life and the post modern condition by the great Rick Roderick the Bill Hicks of Philosophy. What is great about this series is that Rick delivers it such a great way that is very easy to understand, he makes difficult concepts clear and illustrates them in a interesting and engaging way. When I first found these lectures, I had to watch all of them one after another great and I urge you to do the same. Below the film is the transcript of the talk and a summary of the main points, but please watch the lectures first as they deliver a lot. Enjoy and raise a glass to Rick Roderick who unfortunately is no longer with us.

This is the seventh of a great series of lectures about modern life and the post modern condition by the great Rick Roderick the Bill Hicks of Philosophy. What is great about this series is that Rick delivers it such a great way that is very easy to understand, he makes difficult concepts clear and illustrates them in a interesting and engaging way. When I first found these lectures, I had to watch all of them one after another great and I urge you to do the same. Below the film is the transcript of the talk and a summary of the main points, but please watch the lectures first as they deliver a lot. Enjoy and raise a glass to Rick Roderick who unfortunately is no longer with us.

Summary of the lecture:

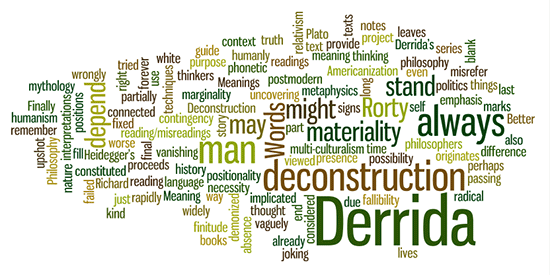

- Richard Rorty may be viewed as an “Americanization” of Derrida: widely considered the postmodern thinkers (perhaps wrongly). Here we will use Rorty as a guide to Derrida.

- Derrida’s emphasis is on fallibility, contingency, finitude; positions partially demonized as relativism, deconstruction, and vaguely connected to radical politics, multi-culturalism, and so on.

- “Deconstruction” originates in Heidegger’s project of the deconstruction of metaphysics, an “uncovering” of the history of Being. Derrida notes, as he proceeds through a series of techniques of deconstruction as reading/misreadings of texts, that philosophers have always tried to fill in the blank in “Being is __________”. But they have failed due to the nature of language which is constituted by difference, materiality of marks and phonetic signs, marginality, materiality. Words do not stand for things, they stand in for them.

- Meanings depend not only on presence but also on absence. Words can always misrefer; a possibility once is a necessity forever.

- The upshot is that there are no final interpretations, no last books. Better and worse readings depend on context and purpose. Meaning is not fixed “humanly” (against “humanism”). Philosophy has always already thought the end of man in thinking the truth of man.

- For Derrida, “man” is implicated in the “white mythology” that is philosophy and whose time is rapidly passing. This leaves the “self”. the “I”, as no more than a vanishing positionality in a text. And this is a long way from the kind of story that might provide us with meaning for our own lives.

- Finally, when reading Derrida, remember, he may just be joking. If he is right, even in part, the same might be said for Plato.

Transcript

In this lecture we are going to do something that from the viewpoint of many people is just simply outrageous. We are going to move from two figures who at least have some things in common, and that’s Foucault and Habermas, both of whom deal with the problems of what I call modernity, and I hope that word hasn’t thrown you too bad, its not such an abstract word. It means the processes by which factories were instituted based on the division of labour and the processes by which institutions came to be rationalised, rule governed across the whole terrain of our social life with few exceptions. That’s the process I have been referring to as modernity, and far from being abstract it’s a part of our everyday life.

In this lecture we are going to do something that from the viewpoint of many people is just simply outrageous. We are going to move from two figures who at least have some things in common, and that’s Foucault and Habermas, both of whom deal with the problems of what I call modernity, and I hope that word hasn’t thrown you too bad, its not such an abstract word. It means the processes by which factories were instituted based on the division of labour and the processes by which institutions came to be rationalised, rule governed across the whole terrain of our social life with few exceptions. That’s the process I have been referring to as modernity, and far from being abstract it’s a part of our everyday life.

It’s called work, it’s called hooking up the telephone, it’s called applying for a job, its called dealing with the IRS, this is modernity, so don’t get lost in the fanciness of the word. That’s modernity. I have argued that it has these pathologies; Foucault has argued it’s had them. We have also argued that it has an upside and I mentioned in an earlier lecture that it’s better to have a toothache in the modern world than before. It’s also better, I mean, across a whole spectrum of medical problems and other kinds, it’s probably better now than it was then. Certainly if you want to get from here to California; it’s better now, because it’s much faster, although that’s probably debatable.

In any case, with that, with a little bit of type about the other lectures, let me begin with this outrageous attempt to try to deal with perhaps one of the trickiest and strangest philosophers – if he is a philosopher – around today, and that’s Jacques Derrida. I think his name has become synonymous with a kind of evil among many analytic American logic chopping philosophers, I mean, Derrida is responsible in many ways for deconstruction; that dreaded enemy that has invaded our literary departments that according to popular mythology tells us that any way to read a book is as good as any other, that there is nothing outside books, that we are always reading and that every reading is a misreading and so on. In my view Derrida believes none of these things that I have just outlined. I am trying to give you the popular demonising mythology about Derrida. I have brought in just one of his books today to show you, but he has written many.

This is “Margins of Philosophy“; its title is very significant for Derrida’s project which is to examine philosophy as a broad longstanding cultural institution stretching back to the Greeks and to try to do so in a framework that reminds us that philosophy so understood is a product of Indo-European languages – to the extent we know what that phrase means – and the product of Western Civilisation. It is not an eternal project in the mind of God, you know, but a project with a certain materiality, a certain history and that many of the most interesting things we will find out about philosophy won’t be from reading it badly, or from saying any reading of a book by a philosopher is as good as any other, but will be by paying attention to the very things the philosopher tried to repress in his text; the things that the philosopher tried to put on the margins, as it were, of the text of philosophy, the things that the philosopher wished to exclude. By drawing our attention to these, Derrida in some ways is like Freud. See, Freud wanted to investigate things like slips of the tongue, jokes in the relation to the unconscious and so on. In a way Derrida’s meta-philosophical project is to investigate philosophy’s slips of the tongue, philosophy’s unconscious witticisms, and so on.

So, this is not an unworthy project and it is rooted in a profound concern with an earlier figure that we discussed at not nearly enough length, and I won’t have nearly enough time to do justice to Derrida now, I just want… if I can dispel a few myths about him I will have done some good in the world. Because even a brief meeting with me convinced me that he was just a fairly jolly French person and certainly not out to tear up the American university system and the image by right wing lunatics conjured up of lesbian deconstruction literary critics dancing at Brown University, burning Chaucer and Shakespeare is utterly a fantasy of paranoid dimensions that surpasses anything that the John Birch Society every dreamed up.

Derrida is an academician, he is a very careful reader, and he has some unorthodox views about language and about the history of philosophy and since I have at least one very good friend who knows his work well, I will draw on some of Louis Mackey‘s remarks today and I will also draw on the Americanised version of Derrida that has been presented to us by Richard Rorty.

Now I am not saying Rorty fully subscribes to everything Derrida says, but Rorty is one of his American admirers. To the extent that he is, that is… as it were, put Rorty in the enemy camp as well – which he is to many analytic and positivist minded philosophers – Rorty is one of the enemy. It’s kind of hard since Rorty’s closest philosophical analogue would be Dewey. In a way he is very American, and in certain ways Derrida’s more American than the Brits that we use as our models for much of the analytic philosophy we do. I’ll try to explain that as I go along.

Okay, let me give you something that I was asked for by a reporter from the Chicago Tribune who was covering the debate over deconstruction, and he went: “What the hell is this stuff anyway?” So this forty-five minute lecture – to an hour – will be an attempt to answer that reporter’s blunt question “What the hell is this stuff anyway that’s causing so much trouble?” I am going to try to answer that.

Well, deconstruction as a term originates in Heidegger‘s project that I have already discussed where I said that Heidegger wanted to perform a deconstruction of metaphysics. A deconstruction of it; not a destruction, but a deconstruction. In other words, to sort of dig through it, underneath it, to read it in such a way that he could uncover, in some sense, the hidden history of Being.

Now, as his project progressed – and that is Being with a capital “B” I just used – as Heidegger’s project progressed, it became more and more obvious to him that it was futile. That Being is – Being with a big “B” – is _____; was a blank that was going to be difficult to fill in. So in the very late Heidegger, when he wrote the word “Being”, he drew a line through it, like that would help. He would write the word, well you could read it, but he would draw a line through it, which he called writing Being under erasure.

Now the point of that was this. This is its connection to modernity and the things we have been discussing, including the self. In the medieval period beings, entities like us found our meaning in being and ultimately in the Being; the highest being. In fact philosophers, I sometimes think that when they use the word “Being” with a big B mean something like God, but just aren’t straightforward enough to say it. In a certain way that seems to be the case.

Now Derrida is a step beyond Heidegger. Derrida’s noticed, as one could hardly fail to notice, that the history of Western metaphysics has been filled with the attempts to answer the question “Being is _____” and to fill in the blank, and if you follow the history of Western metaphysics; Being is the demiourgos, Being is God, Being is whatever is uncovered by the empirical sciences, Being is this, Being is non-existent, whatever we have tried to fill in the blank with we have not yet reached closure. That’s why I said that philosophy is a funny endeavour, it has a 2500 year history of failure and yet it continues. So obviously it’s not quite in the spirit of capitalism to engage in this enterprise. That’s a long time to run a failing business; 2500 years.

Derrida has noticed that this blank can’t be filled in. Being is _____ can’t be filled it, the blank can’t be filled in. Why not? I mean, we want an argument, we don’t want this. I mean, the first thing is that we have noticed that no-one has successfully filled it in. That’s the first thing we notice, that you know, the history of philosophy has not yet presented us with final wisdom, total coverage and ultimate truth. We know that, so that’s step one is to know that. Deconstructive readings try to work this out in detail case by case. You know, different attempts to answer it, and how they failed to answer it. And so deconstructive readings are not a single technique, or even a special set of techniques; they are more like housework.

See, philosophy is not like building a house, where you start with a firm foundation and build it up and you are finished and you walk off and that’s philosophy. Philosophy under the heading of deconstruction is housework, which means every day the floors have to be swept again, the dishes have to be done again, and I’ll be damned, the next day its just like that again, and its just like that again, and its just like that again. So deconstruction, you know, I wanted to compare it as a practice to some other practice it would be housework; it doesn’t get finished. In fact that is at the heart of – I think – the best of philosophy in the late 20th Century, is the idea that it’s not getting finished and it can’t be.

Why have philosophers failed to answer the question Being is _____ – or to fill in the blank – what it Being, with a capital B? Well, Derrida’s take on metaphysics is, as I say, this insight that they have failed to answer the question, but he also has a certain take on language. It’s not exactly a theory of language because Derrida thinks one of those is still to be completed and its still part – the language we speak now – is still part of our metaphysical heritage.

I mean we use metaphysical phrases all the time, even when we don’t think we do. We say “that horse appears to me to be lame” and then we have invoked, you know, the concept of appearance with its long philosophical history. Or you could be a baseball scout and say “that kid has the potential to hit 200″, and now we have invoked the metaphysical language of potentiality with its 2500 year history.

So for Derrida our language is chipped through with metaphysical moments, fragments in or language. There is no way around it. In that sense Derrida certainly wouldn’t say that he has avoided metaphysics. The reason he wouldn’t say that is that he speaks a language. What he wants to do is get a better take on why the language can’t solve the problem that is central to metaphysics and ontology; the problem of answering the question of what is Being, you know.

Now here’s the take. It is the nature of language, and Derrida takes it to be something quite other – language to be quite other – than what many, many other philosophers and linguists take it to be and this is going to be very difficult to do in a short time but I am going to try. For Derrida, language is not – and I will have to do this through a series of negations first – language is not constituted by reference, which is a standard positivist account. In other words, what constitutes reference would be… I used the word “horse” to refer to a horse. Of course, that makes it sound as though what would constitute my talk that it refers namely to the world would be that I am talking about some present horse. My word stands for that horse.

Now you may have noticed there is no horse up here with me. Derrida has noticed that. Words do not stand for things, they stand in for them. Let me make that distinction again. Words do not stand for things, they stand in for them. The noun “horse” is convenient, like the noun “fly”, like the word “potato chip”, the phrase “cow chip”, the name “Neil Bush“; because I have all these words I don’t have to carry around a kit bag of all the entities in the universe to point to when I talk. In other words, the theory of reference makes us think as though what is referred to has to have a kind of presence.

Derrida as usual engages in – and this is a usual deconstructive practice – a kind of reversal. Interestingly enough, that word gets it’s meaning not from the presence of the horse, but from his absence. Now, it also doesn’t get its meaning in isolation. Words are not atomic bits of anything. Words are part of systems of speech. Let me try to make that clear; the way Derrida looks at: systems of language. Let me take Chess as an example; a famous example, one used by Wittgenstein.

If I take a pawn off a chess board and just put it here, you will still know it’s a pawn but it won’t be able to make any pawn moves. To make the right moves, it will have to be on a chess board and deployed in a game. In other words there will be conditions within which it will make sense to move the pawn two squares forward. One of them won’t be to set the pawn on this thing and say: I am going two squares forward because looking ahead of me I don’t know what would count… is that a square? In other words, it’s just not the way the game is played.

With systems of languages they are constituted by the way the words work in these sets of constitutive rules which frequently overlap and which are holistic. For that system to work, the objects so referred to do not have to be present. In fact I just tried to give you an example in which I have pointed out that it’s the absence of objects that make the usage of nouns and languages interesting. I mean, that’s fascinating that we could come here and discuss and entire basketball series without having Charles Barkley or anyone present. This is an indication that absence is one of the constitutive features of language.

Okay another important thing to remember is this. I don’t want to commit the bad abstraction to which philosophy has fallen victim so often by treating language as something other than the following set of things. It is a system, but it has materiality. Language is phonetic sounds that can be heard in finite links, measured and so on, and it is marks – sensible marks – on paper, and here we will attack another view of language. I mean, again, a lot of Derrida’s remarks are negative concerning other views of language.

Just like reference couldn’t be what gives our words their meanings and our uses of them and so on, neither can intentionality of speaker. Now let me try to use one of Derrida’s famous examples. I draw up a grocery list for my wife, I write it down in sensible marks. These are the things we need: toilet paper, we need stuff for the kids, you know, all this… and of course cash so that we can buy fast food for supper. It’s a standard way of shopping. I leave the grocery list and I drive away and I am killed utterly, I am run over by a bus, flattened like a tortilla. My wife comes in, and can my message function in my radical absence? Yes! She can still go to the store, buy the kids food, and maybe only later will they notice “Where’s dad?” and then they hear on the news, you know, “overweight philosopher flattened by truck… tortilla…”

Those signs can work in my radical absence. Now, can they work if I had no intentionality at all in writing them? Yes! Suppose I wrote them three months ago with the intention… well let me make an even simpler example; suppose I wrote them that afternoon with the intention of having my wife leave the house so I could call a lover. Would that make the list ineffective because my intention was misunderstood? No! Many philosophers have wanted to tie meaning to what the speaker and/or language user intends but words have their functions – to use Derrida’s phrase – “their disseminating meanings” apart from those intentions. Now let’s not caricature his claim. This does not mean that we cannot intend; we can, but it means we cannot fix meaning by our intentions.

This is very important when we read a text by an author in philosophy because we are frequently led to ask the question “What did he intend to say?” and the deconstructive reading will lead us in the direction of not “what did he intend to say” but “what are these physical marks”; “how can I interpret these physical marks”. To use that example… and that by the way is an anti-hermeneutic remark; it’s a remark sort of against what might be called the idea that there could be the right interpretation.

This is another important part of Derrida’s take on language and language practices; the idea that there could be the right interpretation. In a way there is no more powerful idea in the discipline of philosophy than the idea that there could be the right interpretation. After all it’s that idea that allows us to give our student B’s and C’s as opposed to the A’s we would make if we had written the paper. It’s what keeps us – it seems – continually to read Aristotle and so on, in order to get them right, finally.

Derrida makes the outrageous claim that in the last analysis there is no such thing as the right reading, the right interpretation. There is no interpretation that can bring interpretation to an end. Good books, really great texts, do not cut off interpretation; they lead to multiple interpretations. Great examples of this would be The Bible, which I think is pretty obvious has not yet reached closure on interpretation. I mean, you know, I grew up in a community where there Baptists, Methodists, Church of Christ, took me a while to get into the city and meet Jewish people, Muslims, others. It became clear to me that reading the Old Testament; was difficult to come up with the right interpretation, and what was wrong was the very idea that there could be the right interpretation.

Now the converse is the claim that people find outrageous but it’s not made by Derrida. That means that since there is no “the right way”, then any way is as good as any other. Now Derrida is not compelled to hold that view and he doesn’t. Not every way to speak and/or read is as good as any other and let me just put it simply: no-one holds that view. Derrida, to the extent that he refuses to play a standard philosophical game just will not play. The fact that there is no final book, you know, one last master encyclopaedia containing all the wisdom, total coverage, final knowledge, the last book, none other ever needs to be written, Derrida considers that a reductio ad absurdum of the idea of perfect interpretation; the right interpretation.

This does not at all mean that we don’t in loose, rough and ready ways judge interpretations… all the time. And this does not at all mean that practically speaking that some interpretations are obviously slightly better than others. Let me return to familiar ones like the traffic light. If it’s red and you see it as green, the outcome can be disastrous; Derrida doesn’t deny it. You know, it’s a bad misreading… bad misreading. But this is a familiar mistake and it is made about a lot of Derrida’s work. Philosophers call someone a relativist by which they mean it’s a person that holds that any view is as good as any other view. My simple response to that is this: that is a straw person argument, no-one in the world believes it or ever has believed it.

No-one – Derrida or anyone else – believes that every view is as good as every other view. That’s only a view we discuss in freshman philosophy class in order to quickly refute it. I mean no-one believes it. There are no defenders of the view and since this tape will be going out, if we run into one it will be interesting, but we will likely find that person in one of the institutions Foucault discussed rather than in some seminar, okay. That’s where we will find them, if anybody believes that. No, Derrida’s kind of slippage is to remind us that the text of philosophy is not fixed; cannot be fixed. It is of the nature of the text of philosophy and its relation to language that we cannot fix it once and for all. In a way it’s like the leaky ship where we haven’t got anything to stop the leak so we just keep bailing. I mean, the leak is in the language.

One way to give you an analogy that may make it come alive and be simpler for you – and that’s been hard for me to do with a philosopher who is very difficult like Derrida – is to think about it in the context of the way that Augustine attempted to develop a rhetoric about God, and then Augustine realised that it was already impasse to use finite human marks and sounds to praise an infinite being, entirely separate from those finite marks and sounds; so he was driven to silence. If one were to take that same picture of language without the thought of developing a rhetoric of God, but left with just the finite marks and sounds and no inner teacher – Christ the inner teacher – to tell us when our signs worked and when our words referred, then we would have a language that operates by disseminating meaning, by moving meaning, by shifting it.

So if you were to have for example Derrida criticise Habermas, Habermas would say something like this, he would go “Understanding is a condition for our linguistic practices” Derrida would respond “If that is so, then so is misunderstanding equally constituentive” Understanding won’t make sense conceptually unless misunderstanding does. They are correlatives – does that make sense? Well I hope it makes sense; I am asking a rhetorical question now about a philosopher who does rhetoric, but anyway… as well as argument.

So these are the kinds of things that irritate people. In addition – and this is I think the take on language that he has – basically words can always misrefer. They could always misrefer; our meaning could always go astray. Even when we point – this is the most simple example analytic philosophers use – I say “Get me that cup there” and you could still pick up this one instead of this one. Pointing won’t even guarantee a reference, and if it’s possible to misrefer, if it’s possible to misread, if its possible to misunderstand, then it belongs to that structure I have called language to do those things, because a possibility once is a necessity forever. Let me say that again. A possibility once – when we speak in structural terms – is a necessity forever. This is what makes original sin so interesting. Human beings who don’t sin are still sinners in the Christian tradition because the possibility once is the necessity forever; a possibility once is a necessity forever.

Now these are subtle views; Derrida is frequently caricatured for these views. We would all like to hold theories of meaning that made fundamental experiences like pointing what meaning was about and so on. But I don’t think Derrida’s views lead to… what I would like to give you now is what I would call the “upshot” of some of the views, and I don’t think that they are that outrageous. The upshot, as I have said, is that there will be no final interpretations in philosophy, and I think that the history of metaphysics bears that out; the history of philosophy. There will be no last books. Even The Bible wasn’t a last book; I wonder how many commentaries have been written on it?

There will be no last books, no final commentaries, no ends to the flows of information. Meaning is not fixable or fixed even humanly in a certain way. Since we speak the language of metaphysics in a certain sense – I have already talked about potentiality, appearance and so on – in a strange way language has a power to operate in the radical absence of man. I used the example of my own death and the list for my wife, but there are many other examples. You find, as it were, a monument in stone and you can decipher the cuneiform, and that idea of man has disappeared for ages of time, but the words as materiality still can be interpreted; not finally, but they still have their effects… their effects.

Now, to some of the political upshot of Derrida and why I think he does outrage people. Looking at philosophical language as metaphorical – largely metaphorical – in fact, if you understood what I just said about Derrida you will see that the sense in which it is frequently said that for Derrida all words are metaphorical. By that he means that no word is the thing. The word “horse” is not a horse. The word “cat” is not a cat. The word “neutrino” is not itself a neutrino. There are some exceptions, but not really. Is the word “word” a word? No, because I have mentioned it and not used it. It has now become a token of a word.

So, what I am trying to say here is that words are not things. That the attempt that philosophers have made to hook words to the world has failed but it’s no cause for anyone to think we are not talking about anything. See this doesn’t make the world disappear, it just makes language into the muddy, material, somewhat confused practice that it actually is; or that at least according to Derrida it actually is.

Now here is some of the upshot of it that I think has caused people to be upset. Not only this business about better and worse readings, to which we will go “What is a better reading of something?” “Damnit, nothing means anything anymore”; these are some of the things that upset them. “Everything can’t be a metaphor, I mean, sometimes I mean what I say, damnit, and I just mean it” I mean these kind of frustrated remarks by professors who have been around a long time. The most irritating of all, and I think I will read a short passage if I have time – am I running? I think my time is running okay – I’ll take a very short passage because it is particularly irritating. It’s in one of Derrida’s finest pieces of writing if I can myself find it…

In his article “White Mythology” Derrida makes a point about the metaphorical nature of philosophical language, and I think he makes it in a rather humorous way; he uses a story from Anatole France in which Anatole France is giving an analysis of a philosophical passage and he takes the following passage – Anatole France does, Derrida is just discussing it – “Wherefore I was on the right road when I investigated this sentence…” and here is the sentence investigated by Anatole France: “…’The spirit possesses God in proportion as it participates in the absolute’…” I think that’s actually a sentence from Hegel.

Now, Anatole France goes on to say “…it was important to see that these words were signs that had, as it were, changed meanings and shifted through time, it was important that we were able to do a translation: ‘The spirit possesses God in proportion as it participates in the absolute’ what is this if not a collection of little symbols much worn and defaced, I admit, symbols which have lost their original brilliance…” – how they must have sounded maybe in Greece, maybe even in 19th Century Germany – “…their original brilliance and picturesqueness, but which still by the nature of things remain symbols, and I have been able without sacrificing fidelity to substitute one for the other…” – To, as it were, update this into a more modern – “…in this way I have arrived at the following translation: ‘The breath is seated on the shining one in the bushel of the part it takes in what is altogether loosed, or subtle’”

And then we get the next step of translation: “‘He whose breath is a sign of life; man, that is, we will find a place – no doubt after the breath has been exhaled – in the divine fire, source and home of life and this place will be meted out to him according the virtue that has been given him, by demons I imagine, assuming abroad his warm breast this little invisible soul across the free expanse; the blue sky, most likely’“.

“And now observe…” – says Anatole France – “And now observe, the phrase has acquired quite the ring of some fragment of a Vedic hymn…” – just by returning it to its sort of original meanings of absolute, God, and so on, just by returning it to those meanings when they had their brilliance and their sort of life… time… because now it sounds like a Vedic hymn “…and even smacks of ancient oriental mythology. I cannot say that I have restored this myth in full accordance with the strict laws that govern all language, but no matter for that, enough if we have found that symbols in a myth in a sentence that was always essentially mythical and symbolic in as much as it was metaphysical.”

“I think I have tried to make you realise one thing…” Anatole France says “…that any expression of an abstract idea can only be by analogy or metaphor…” – can only be by analogy or a metaphor – “…by an odd fate the very metaphysicians who think to escape the world of appearance are constrained to it perpetually by allegory, metaphor and analogy. They are a sorry lot of poets…” – a sorry lot of poets – “…they dim the colours of their ancient fables and they are themselves but the gatherers of fables. They produce White Mythology.”

Now Derrida comments “A formula, brief, condensed, economical and mute has been deployed in an interminably explicative discourse, the derisive effect which has always produced by the translation of anything occidental into the oriental idiogram”

[alternate translation, not from the lectures but taken from here]

Wherefore I was on the right road when I investigated the meanings inherent in the words spirit, God, absolute, which are symbols and not signs.

“The spirit possesses God in proportion as it participates in the absolute.”

What is this if not a collection of little symbols, much worn and defaced, I admit, symbols which have lost their original brilliance, and picturesqueness, but which still, by the nature of things, remain symbols? The image is reduced to the schema, but the schema is still the image. And I have been able, without sacrificing fidelity, to substitute one for the other. In this way I have arrived at the following:

“The breath is seated on the shining one in the bushel of the part it takes in what is altogether loosed (or subtle),” whence we easily get as a next step: “He whose breath is a sign of life, man, that is, will find a place (no doubt after the breath has been exhaled) in the divine fire, source and home of life, and this place will be meted out to him according to the virtue that has been given him (by the demons, I imagine) of sending abroad this warm breath, this little invisible soul, across the free expanse (the blue of the sky, most likely).”

And now observe, the phrase has acquired quite the ring of some fragment of a Vedic hymn, and smacks of ancient Oriental mythology. I cannot answer for having restored this primitive myth in full accordance with the strict laws governing language. But no matter for that. Enough if we are seen to have found symbols and a myth in a sentence that was essentially symbolic and mythical, inasmuch as it was metaphysical.

I think I have at last made you realize one thing, Aristos, that any expression of an abstract idea can only be an analogy. By an odd fate, the very metaphysicians who think to escape the world of appearances are constrained to live perpetually in allegory. A sorry lot of poets, they dim the colors of the ancient fables, and are themselves but gatherers of fables. The produce white mythology.

A catchphrase-brief, condensed, economical, almost dumb is deployed in a speech consisting of interminable explanations. It stands out like a schoolmaster. It produces the laughable effect always given by the wordy and arm-waving translation of an oriental ideogram. Here is a parody of the translator, a metaphysical naivety of the wretched peripatetic who does not recognize his own figure, and does not know where it has led him.

Anyway, that’s supposed to be funny to really, you know like, funny types of people – academics mainly – but they didn’t find it amusing because in the history of philosophy it’s the beginning of an argument. That many of these words are words… I said “Being”, if we went back would be “God”, if we took that word back far enough it would be “The breath of the great beast of the east”, took that back it would probably be “The tree that stands the tallest” and so on.

Once we have translated all that out, we do have kind of a Vedic hymn, and philosophy according to Derrida is doomed, as it were, if you want doomed to be the word; I think it actually can be playful, and Derrida is witty about it. It’s not sad to him that philosophy cannot become finally a great science or anything. They are doomed to be a more or less sorry lot of poets, I mean, the better the poet the better the wit, the better the philosophy in some cases for Derrida. He clearly likes a good joke, and part of the last argument that I – well it’s not an argument, it is an economical statement, mute and so on – is supposed to be a joke too. But then the political intent is clear underneath it.

If philosophy is white mythology, what’s to keep us from teaching other mythologies at the university? Like women’s mythologies and black mythologies and Hispanic mythologies and oriental mythologies. I hope you are beginning to see why Derrida began to upset people. If this was true, it wouldn’t mean that white mythologies had lost their interest or that they weren’t profound and worthy of study but it would mean they were no more so than black mythologies, Hispanic mythology, women’s mythology. If I were to look for examples of Derrida’s marginality of the spoken or the written word; the trace, the gramme, the many… and I have left out many sophistications here, who cares, I am not French, I don’t eat soufflé’s, forget it, I am trying to get this across in the spirit of that Chicago Tribune article.

This is the disturbing part to academics, is it opens up this road within which many other mythologies, if you will, could be spoken with equal right… with equal right as the dominant ones have been in the past and I think that is not at all a bad effect that Derrida has had. The fact that he has a sense of humour I don’t hold against him. I wish more academics did. I think it’s pedagogically useful not to be a damn bore all the time… and just, you know, put people to sleep… is pedagogically useful. After all, you know, professors and lecturers have to compete with MTV, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jurassic Park.

So, I hardly think it’s in our interest to be boring, and ah, that’s one thing Derrida certainly is not. And, it’s nice to encounter in the dark days that lay ahead as I eh, trudge through what a self can be, it’s nice to encounter a playful spirit. Derrida is very troubled about what the self might even be. But, he is troubled in that playful way that Nietzsche is troubled when he is at his best. And eh, so, ah, I hope that I could at least interest you in ah, looking at something of Derrida’s. In fact, I will leave you with one last little joke of Derrida’s.

So much work has been spent, and so much time has been spent interpreting Nietzsche, and now of course paradoxically Derrida, because these things go on and on. Ah, he wrote a little book called “Spurs: Nietzsche’s Style” and in it, he imagines that Nietzsche left behind, among his many papers a little scrap of paper that says: “I forgot my umbrella”. Then Derrida goes through a long, complex way that an academic interpreter would try to fit this brilliant aphorism of Nietzsche’s into the body of his work. I mean, after all, it might just mean “I forgot my umbrella”, but on the other hand…

And, of course, by the time – and this is a short little book I think you could enjoy – by the time that Derrida’s finished, I think that one has at least learned to be an interpreter with more grace, and with a little bit more poetry, and perhaps it would free us for richer, more multicultural, more diverse, and more humane interpretations… if we would free ourselves from the myth. The invidious myth that there is a right way to read a book – one. A right civilization to belong to, as though we chose it. A right gender to be, as though we could pick it. A right class to belong to, as though we chose those things. A right race to be. A certain mythology preferable to others, as in White. Which according to some African-American scholars today – insofar as it’s Greek – was stolen from the Africans in the first place. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but it’s certainly an interesting conjecture, and it’s one in which the readings and the battles of interpretation, as Derrida points out, will not stop. There won’t be a last book, and I am afraid that also warns you that in this class as in many others, there will not be a last word. Thank you very much.

Thanks to Rick Roderick.org